Paper presented to The Land: Past, Present, Future symposium at the Centre for Professional Development, Charles Sturt University, hosted by Macquarie University’s Centre for Media History and CSU’s School of Communication and Creative Industries, 5-6 May, 2011.

Also see the more scholarly article published in the international peer reviewed journal Rural Society 21:2, pp. 136-145, February 2012 [pdf 92KB] Read it here >>

FOUND DROWNED

For about a week it had been known that Mrs Wm. Foster was missing from her home, but there was no reason to suspect anything more than that she had gone away, hence some little excitement was caused in town about midday on Friday when it became known that her body had been found floating in the lagoon at the back of the Chinaman’s Garden opposite the new racecourse. The police brought the body to Mrs Ryans Carlton Hotel, where it was examined by the Government Medical Officer, Dr. McDonnell, and from which it was interred on the following day. [1]

This brief paragraph in the Forbes & Parkes Gazette of Tuesday 18 October, 1898, and the inquest report which follows it, [2] are the only surviving accounts of the death of one of Australia’s most iconic women.

Portrait courtesy the State Library of Victoria. Wood engraving published in The Illustrated Australian News, July 3, 1880, David Syme & Co, Melbourne.

In 1880, the year her brother Ned’s bushranging career ended, Kate was a teenage celebrity, both praised and vilified in the colonial press. People flocked to catch a glimpse of her. They paid money to see her ride, and bought postcards of her wearing a black silk riding habit. And yet, by 1898, she had become all but invisible. In the Forbes & Parkes Gazette she was simply the late and estranged wife of a local man, William Foster, a horse-tailer on a large pastoral station on the Lachlan River.

A married woman had no independent legal status at this time, of course, so Kate Kelly’s invisibility need not necessarily be considered surprising. Yet the few documents which remain to trace her life in the historic record strongly suggest that both she and her husband actively connived to hide her personal identity and family history. The bride’s name on the couple’s marriage certificate is given as Ada Kelly, for example; the birth certificates of each of their children similarly smudge her identity; and on her death certificate her parents are named as Thomas Kelly and Mary McClusky, rather than John Kelly and Ellen Quinn. (Mary McClusky was Ellen’s mother.) One has to conclude, therefore, that Kate wanted to be invisible. She settled on the Lachlan in the mid-1880s to escape her past.

Given the inconsistencies in the historic record, however, how do we know that “the right Kate came to Forbes”, as a headline in the Forbes Advocate observed nearly sixty years after her death? [4] And how is she remembered in this small country town?

There is no-one alive today who actually knew Kate Kelly, and nor does she have any descendants in Forbes to tend her memory. Her brother Jim Kelly collected her three surviving children soon after her death and took them back to the family selection on Eleven Mile Creek near Greta, where they were raised by their maternal grandmother Ellen. And yet Kate Kelly remains very present in Forbes’s collective memory, nothwithstanding her own attempts to hide her identity. [5] Locals still recount family stories, which may or may not be true, about a great-grandmother who was the last person to have seen Kate alive, or who gave her a glass of water as she walked towards the lagoon, for example; or stories about great-grandparents who employed her as a home-help or domestic servant. In these anecdotes Kate Kelly is remembered as a “nice girl” and “a hard worker. [6] But her husband is remembered very differently.

William “Bricky” Foster’s grave in the Anglican section of Forbes Cemetery, some distance from where his wife is buried. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 5 December, 2008.

Will or Bricky Foster died in Forbes in 1946, having outlived his wife by nearly half a century, [7] so there are still old timers alive today who knew him personally. He is remembered as being violent and cruel, a heavy drinker, and a “mongrel” of a man, as one local told me. [8] And there are many things that are still not said about Brickie Foster, especially concerning his relationship with Kate. But we’ll come to that soon enough.

Remembering is now understood to be a creatively dynamic and performative process. In the emerging field of memory studies scholars differentiate between the localised and unstable recounting of lived experience, hearsay and confabulation, or “communicative memory” I’ve been describing, and “cultural memory”, a more stable, although equally selective evocation of past events, which are shared and passed on, generation to generation, through the print and electronic media, literature, film, web sites, festivals, rituals, exhibitions, national epics, monuments and other representations. [9] Cultural memory can thus be described “as an ongoing process of remembrance and forgetting in which individuals and groups continue to reconfigure their relationship to the past and hence reposition themselves in relation to established and emergent memory sites.” [10]

This complex dynamic is still under-theorised and poorly understood, but the strategy of dispositif analysis, as exercised in different contexts by Foucault, Baudry, Deleuze, Agamben and others, is proving to be a useful intellectual tool. [11] (Dispositif is often very inadequately translated to English as ‘apparatus’. [12] ) In cultural theory, the term refers to “a tangle, a multilinear ensemble” of diverse elements and the relationships between them. [13] Laura Basu, who introduced the term to memory studies in her recent analysis of the mythologisation of Kate Kelly’s brother Ned, explains it thus:

A single representation in itself can exemplify a mode of remembering; however, no text, genre or technology works alone to form a cultural memory. Most cultural memories are made up of many different representations in a variety of genres and media. Moreover, it is not only a collection of representations that makes a memory but their constellation: their positioning in relation to each other. The idea of a memory dispositif allows us to begin to map those constellations and understand how they function. [14]

My discovery of Basu’s work represents a breakthrough in my attempts to understand the mythologisation of Kate Kelly in central western NSW, a dynamic in which I am personally immersed through my Kate Kelly Project.

The ‘Victorian Kate,’ the teenage celebrity who is eulogised in C19th bush ballads – The daring Kate Kelly how noble her mien/ As she sat on her horse like an Amazon queen – was as well known north the Murray as she was in Victoria. This Kate, rather than the later ‘Forbes Kate’ I’m interested in, featured prominently in popular fiction and non-fiction of the era, such as F. Hunter’s The Origin and Destruction of the Kelly Gang, first published in 1896, for example. [15] In 1911, the Sydney Sun ran BW Cookson’s very romanticised feature articles, ‘The Kelly Gang From Within: Survivors of the tragedy interviewed’, to add new narratives to the memory dispositif in New South Wales and beyond. [16] Cookson’s interviewees included Kate’s mother Ellen Kelly and her brother Jim, both of whom confirmed that Kate had died in Forbes and was not living in Queenland, as many people apparently believed at the time. Cookson’s stories also repositioned Kate at the very centre of the Kelly legend. As Ellen Kelly tells him:

The trouble began over a young constable named Fitzpatrick. That was in April 1878. He came to our place over there and said he was going to arrest Dan. He started the trouble. He tried to kiss my daughter, Kate. He had no business there at all, they tell me–no warrant or anything. If he had, he should have done his business and gone. [17]

And, in Jim Kelly’s version of the story: “Dear, loyal, brave little Kate! … Of course she helped her brothers in their trouble. Was it not on account of her—to protect her—that they got into trouble?” [18]

A year later, in 1912, the Advocate in the town of Orange, in central NSW, published Jack Bradshaw’s ‘The only true account of the Kelly gang leading up to their capture and death by a perfect authority : also an interview with old Mrs Kelly, Mr. James Kelly and family’. [19] Bradshaw claimed that he wrote this long-titled booklet to “vindicate the characters of Ned and Dan Kelly”, after an unfavourable letter or article by Ambrose Pratt was published in the Bathurst Times. Bradshaw romanticised Kate and her sisters: “the Kelly girls were noble, affectionate sisters, the greatest heroines that Australia has ever produced.” He even provided dialogue for Kate’s encounter with the dastardly Constable Fitzpatrick, to add yet more mythic elements to her memory dispositif. [20]

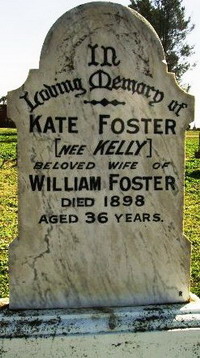

Some years later, members of the Kelly family asked Hugh McDougall, the manager of Warroo Station on the Lachlan River near Forbes, and the man credited with bringing Kate to the district in the mid-1880s, to erect a headstone over her grave. [21] We can infer this from a personal letter from Hugh McDougall to Kate’s brother-in-law in Forbes, Arthur Foster, who had promised to look after the grave site. The letter is dated 6 December 1923, or possibly 1925. [22] The simple headstone McDougall commissioned proudly acknowledges Kate’s maiden name, and remains today as her most permanent memorial. People still visit it, some to lay fresh flowers in her honour, and every couple of decades admirers restore or renovate it.

In 1954 new threads were added to the ‘tangle’ that is the cultural memory of Kate Kelly in Forbes, following the publication of Frank Clune’s popular non-fiction, The Kelly Hunters: The authentic, impartial history of the life and times of Edward Kelly, the Ironclad Outlaw. [23] Clune’s book detonated an explosion of letters-to-editors around the country, one of which was written by another of Kate’s brother-in-laws, Edward R (Ted) Foster, of Lidcombe, to the Editor of The Sunday Truth. Ted Foster wanted to belatedly present what he called “the facts” about Kate. [24] Her death in Forbes from “misadventure”, as he called it, “cut short a colourful life of a woman who possesed [sic] a wonderful disposition and devotion to home and children together with a heart of gold any Australian would be proud of”. The letter also revealed to the public that Kate’s only son Frederick “gave his life for King and country in 1916 at Bullecourt France”. The lad’s military records confirm this.

Back in Forbes, in the following year, 1955, the Advocate published an interview with an Edward Ford who reiterated the old bush yarn that “the real Kate Kelly” had settled in Queensland. [25] This was refuted a fortnight later by a local woman, Mrs Rae: ‘Right Kate Came Here Says Friend’, as the headline put it. [26] Ted Foster soon entered the debate with a letter to the Forbes Advocate headed ‘True Story of Kate Kelly’. [27] He may also have been the source of a story about a theatrical performance about the Kelly Gang in Forbes, by a Mr Coles and his troupe, which Jean Bedford used in her 1982 novel Sister Kate, [28] although I have yet to find convincing evidence to prove that such a troupe actually visited Forbes around the time Kate disappeared.

And now I am adding to this rich cultural memory dispositif myself through the Kate Kelly Song Cycle, a musical collaboration with composer Ross Carey. Our New Music composition will be premiered in Forbes on 4 September, 2011, beside the very lagoon from which Kate’s body was recovered in 1898, as the headline act for the inaugural Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival, and the opener to the NSW State Landcare and Catchment Management Forum.

Ross Carey and I are very consciously introducing new elements to the dispositif with our Song Cycle, and reviving a number of ‘forgotten’ stories — about the Wiradjuri people who were still very present in and around Forbes in 1898, for example, and the many Chinese migrants who lived in and around the town, including grocer Quong Lee who owned the shop where Kate Kelly and the Fosters almost certainly shopped. Indeed, in our Song Cycle, it is Quong Lee who tells Kate’s story from a Cantonese-Australian perspective.

But there is one more story I have uncovered to add to the still-evolving cultural memory of Kate Kelly in Forbes.

In May 1898, five months before her death, the Forbes and Parkes Gazette reported that a William Foster appeared before the Forbes Police Magistrate at the Police Court and pleaded guilty to using indecent language. According to the Gazette, “Constable Webster stated the language was used in his own house to his wife, within the hearing of the public.” Foster was fined five pounds, four shillings and ten pence, and in default, three months in gaol. [29]

Wife bashing was not a criminal offence at this time, although using indecent language was. And whatever was happening in the Foster household leading up to the charge in May 1989 was considered by someone to be serious enough to call the police. After that date, Bricky Foster moved to Burrawang Station and rarely saw his wife and children. He testified at the inquest into her death, however, that he visited them on the night before she disappeared. [30] So what happened while he was with Kate that night? And did he return to Burrawang the following morning, as he claimed to have done in the inquest?

We don’t know, and the matter appear not to have been raised by the coroner. It is tragic to think, however, that Kate Kelly who, in her youth, was the victim of what some have called a Land War, the conflict between Squatters and Selectors, might also have been, in adulthood, yet another casualty of domestic violence, the ongoing war between men and women.

© Merrill Findlay

Forbes, May 2011

More on Merrill’s Kate Kelly Project >>

Also see In Memory of Catherine Foster >>

Endnotes

[1] Forbes and Parkes Gazette, Tuesday, 18 October 1898, p. 2. Also see https://merrillfindlay.com/?page_id=320, last accessed 8 May, 2011.

[2] NSW Public Records Office advises that no records from investigations into the death of Catherine Foster, nee Kelly, in October 1898, have survived: indeed, the Public Records Office apparently has no inquest papers for the entire year 1898-99. Pers.Com., Rachel Hollis, Archivist, Public Access, State Records, State Records Authority of New South Wales: Email to Merrill Findlay dated Wednesday, 14 May, 2008.

[3] Australian folk song: Ye Sons of Australia. See http://ozfolksongaday.blogspot.com/2011/04/ye-sons-of-australia.html, accessed 8 May, 2011.

[4] Forbes Advocate, ‘Right Kate Came Here Says Friend’, Forbes Advocate, 12 August 1955, Forbes, NSW.

[5] ‘Collective memory’ is a term introduced by French theorist Maurice Halbwachs and others in the first half of the twentieth century. Assmann, J. and J. Czaplicka (tr), 1995, ‘Collective Memory and Cultural Identity’, New German Critique 65, pp. 125-133; Rigney, A. 2005, ‘Plenitude, scarcity and the circulation of cultural memory’, Journal of European studies, 35:1, p. 12; Olick, JK, 2008, ‘Collective Memory’, International Encyclopedia of Social Sciences. W. A. Darity, Gale, pp.7-8.; Confino, A, 1997, p. 1392, ‘Collective Memory and Cultural History: Problems of Method’, The American Historical Review, 102:5, pp. 1386-1403.

[6] Forbes Advocate, ‘Right Kate Came Here Says Friend’, Forbes Advocate, 12 August 1955, Forbes; Pers. Com., John Reynolds, Forbes 12 Sept. 2008.

[7] Forbes Advocate, ‘Obituary: William Foster’, 9 August 1946.

[8] Pers.Com, John Reynolds, Forbes 12 Sept. 2008.

[9] Assmann, J. and J. Czaplicka (tr), 1995, p. 129, ‘Collective Memory and Cultural Identity,’ New German Critique, 65(Cultural History/Cultural Studies), pp.125-133; Jeanette Rodríguez and Ted Fortier, 2007, Cultural memory: resistance, faith & identity, University of Texas Press, pp. 7-14; Ann Rigney, 2005, p. 14, “Plenitude, scarcity and the circulation of cultural memory,” Journal of European studies, 35:1.

[10] Erll, A. and A. Rigney, 2009, p. 2, Mediation, remediation, and the dynamics of cultural memory, Walter de Gruyter.

[11] Basu, L. 2009, ‘Towards a Memory Dispositif: Truth, Myth, and the Ned Kelly lieu de mémoire, 1890-1930’, in A. Eril and A. Rigney, Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory, Walter de Gruyt, pp.139-156.; Basu, L, 2008, “The Ned Kelly memory dispositif, 1930-1960: Identity Production”, Traffic 10, pp 59-74; Basu, L, 2010, Remembering an iron outlaw: the cultural memory of Ned Kelly and the development of Australian identities, PhD Thesis, Faculty of Humanities. Utrecht, Utrecht University; Basu, L, 2011, “Memory dispositifs and national identities: The case of Ned Kelly,” Memory Studies, 4:1, pp. 33-41.

[12] Basu, L. 2011, p. 35, “Memory dispositifs and national identities: The case of Ned Kelly,” Memory Studies, 4:1, pp,33-41.

[13] Deleuze cited in Basu, L, 2008, p. 59, “The Ned Kelly memory dispositif, 1930-1960: Identity Production.” Traffic 10, pp 59-74; Basu, L, 2011, p. 34,”Memory dispositifs and national identities: The case of Ned Kelly,” Memory Studies, 4:1 pp. 33-41.

[14] Basu, L. 2011, pp. 35-36, “Memory dispositifs and national identities: The case of Ned Kelly.” Memory Studies, 4:1 pp. 33-41.

[15] Hunter, F. 1900 [1896], The Origin and Destruction of the Kelly Gang, Gary Dean, http://www.nedkellysworld.com.au/archives/the_origin_and_destructio_%20of_the_kelly_gang.doc, accessed 30 April 2011.

[16] Cookson, BW, 1911, ‘The Kelly Gang From Within: Survivors of the tragedy interviewed,’first published in The Sun, 27 August – 24 September 1911, Sydney, http://www.nedkellysworld.com.au/archives/the_origin_and_destructio_%20of_the_kelly_gang.doc, accessed 30 April 2011.

[17] Ibid., p. 6

[18] Ibid., p. 16

[19] Bradshaw, J, 1912, The Only True Account of the Kelly Gang, Advocate Print ,Orange, NSW.

[20] Ibid. p. 14, 17-18

[21] Foster, ER, 1955, ‘True Story of Kate Kelly’, Forbes Advocate, 21 October 1955, Forbes, NSW.

[22] McDougall, H, 1923 [or 5], Letter to Arthur Foster. Warroo, Forbes, Correspondence from Hugh McDougall, Warroo Station, to Arthur Foster, Forbes, dated 6 December, 1925, in the possession of Robert Reade, Forbes. Sighted 25 February 2008 and photographed with permission.

[23] Clune, F, 1954, The Kelly Hunters: The authentic, impartial history of the life and times of Edward Kelly, the Ironclad Outlaw, Angus & Robertson.

[24] Foster, E, 1954, Letter to the Editor, Sunday Truth, dated 20 October, 1954. Handwritten version on the Foster Family Collection, c/- Karen Purnell, Qld.

[25] Forbes Advocate, ‘Veteran’s Tale of Kate Kelly,’ Forbes Advocate., 29 July 1955, Forbes.

[26] Forbes Advocate, Right Kate Came Here Says Friend, 12 August 1955.

[27] Foster, E. R. True Story of Kate Kelly, Forbes Advocate, 21 October 1955.

[28] Dunstan, K, 1980, Saint Ned: The story of the near sanctification of an Australian outlaw, Methuen of Australia. p. 22.

[29] Forbes and Parkes Gazette,1898, Fined, Forbes and Parkes Gazette, 21 May, Forbes.

[30] Forbes and Parkes Gazette,1898, Found Drowned [Report on the Magisterial Inquiry into the death of Kate Kelly], p. 2, Forbes and Parkes Gazette, Tuesday 18 October, Forbes. See https://merrillfindlay.com/?page_id=320, last accessed 8 May, 2011.

Page created 27 January 2011 (with abstract only). Last revised 17 May, 2011. Permalink: https://merrillfindlay.com/?page_id=1979