Hayatabad, Peshawar, Pakistan, October 2006

For my Afghan friend Ariana (not her real name)

I’m at my friend Ariana’s flat in Hyattabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan, near the border with Afghanistan. Singer-songwriter Farhad Darya is crooning about mountain streams, shepherds and fat-tailed sheep on cable TV. “He’s not really singing about sheep and shepherds,” Ariana explains. “More about his hopes, his dreams for a peaceful future in our homeland.”

Darya is a national hero in Afghanistan. His Kabul Jaan (Beloved Kabul) was the first song played on national radio in 2001 after the collapse of the Taliban regime: Let me sing limitless songs/ Limitless songs for the agony of the Afghans/ For my homeless wandering people/ Let me sing from Iran down to Pakistan.[1] Music had been banned under the Taliban, so Kabul Jaan heralded a new era. Darya co-wrote it with his friend, the poet Qahar Asi, who was killed in a rocket attack on his home in Kabul during the civil war of 1994.

Cable TV brings news from Afghanistan to Ariana’s exiled family in Hayatabad, Pakistan. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

Darya is followed on the family’s little screen by a fresh-faced young newsreader in a snappy suit, white shirt, and blue and orange striped tie. An Afghan airline company has been banned from European airports because its planes were too old. A customs officer has been arrested at Kabul airport because he found too many drugs and contraband. (“He was too honest!” Ariana editorialises, with a brittle laugh.) “And look, there’s Paktiya, our province. The Taliban are still very active there,” she says.

Yes, I’d heard of Paktiya. US invasion forces had fought a big battle against al Qaeda and the Taliban in Paktiya’s Shah-i-kot Valley in 2002.[2] And not long before I arrived in Peshawar, the province’s governor, Hakim Taniwal, an Afghan-Australian, had been assassinated by a suicide bomber. “Afghan-Aussie governor killed,” The Sydney Morning Herald’s headline announced.[3] Hakim Taniwal and his family had fled as refugees during the Soviet occupation and found sanctuary in the Melbourne suburb of Dandenong. He was killed while trying to restore peace.[4]

And now a Taliban commander and three civilians have been killed in an aerial raid on a village on the Pakistan side of the border, the newsreader says. The screen fills with images of bearded men in turbans: “They’re discussing the Durand Line,” Ariana explains. “They don’t recognise it as an international border and want to abolish it, or at least move it, so it no longer divides the Pashtun nation.” As an ethnic Pashtun herself, she sympathises with the turbaned men’s aspirations for a single, undivided homeland. And then a change of pace: a gaggle of Indian dancers shimmying across the screen in an ad for a popular Bollywood serial.

Hayatabad was built in the mid-1970s as a suburban oasis for Peshawar’s upper and upwardly mobile classes. It was named for Hayat Khan Sherpao, a charismatic politician and co-founder of the Pakistan People’s Party, assassinated in 1975 while making a speech at Peshawar University. A bomb exploded beneath his podium. By the time of my visit, Sherpao’s namesake town had become a sanctuary for thousands of rent-paying middle or upper-class Afghan refugee families like Ariana’s. Most of these tenants had at least one member in business or employed in a white-collar job in Peshawar, and/or they received remittances from family members living overseas. I suspected, however, that, this being Pakistan, some of the highest rents were being paid from less legitimate sources.

Ariana at work in 2006. Photo by Merrill Findlay.

Ariana worked as a translator and community liaison officer with an international humanitarian organisation. Her salary, plus remittances from siblings in the US and Germany, supported six people: her mother, three more siblings, an uncle and herself. The combined family income enabled them to live in modest respectability in a four-room flat in a modern two-storey building in one of Hayattabad’s quietest streets. Ariana was nevertheless very concerned about her own and her family’s future. She was one of the thousands of Afghans who had not been enumerated in Pakistan’s 2005 Census of refugees; in her case, she was fdoing remote fieldwork throughout the Census period. Therefore, she could not obtain a Proof Of Registration identity card (PoR), and without a PoR, she could be deported back to Afghanistan as an illegal alien. What would happen to her family if that happened? What would happen to her?

Ariana’s mother is in their small kitchen with her youngest daughter preparing iftar, the traditional sunset snack to quell the Ramazan hunger pangs before the evening meal. We sit on large musk pink and gold cushions on the living room floor, waiting for the sun to set. The only other furniture in the room is a couple of glass display cabinets for the family’s few remaining treasures and a wall of built-in cupboards and shelves for the television and the family photographs.

Ariana’s mother was my age. She grew up during the reign of King Zahir Shah in one of Afghanistan’s rare eras of peace. She was still a teenager when she married in the late 1960s. Kabul was known as the Paris of the East at this time. Her wedding photographs show a shy dark-haired girl in a white European-style wedding gown with long sleeves and a full skirt. Her tulle veil is falling from a crown of tiny white filigree blossoms. She’s wearing light eye shadow, lipstick, heavy gold bracelets and rings, and is carrying a smart white handbag. Her new husband is tall, broad-shouldered and clean-shaven, with short wavy hair. He is standing beside her in a stylish grey pin-striped suit, white shirt and a wide 1960s purple and blue silk tie. Although their marriage was arranged, this photograph depicts them as a handsome and modern young couple. A second photo shows them with their extended families. All the men are clean-shaven and wearing suits and ties, or military uniforms, except for one elderly gentleman from the family’s ancestral village. He has a long white beard and is dressed in traditional tribal garb, including a small dark turban. The few women in the photos are all lightly veiled with uncovered faces. Another set of photos shows the couple in traditional tribal wedding garb: he in a baggy long white tunic and pants, a dark blazer and a decoratively wrapped turban; she in a black velvet chador lavishly embroidered with gold thread over a brightly embroidered bodice, a full purple skirt trimmed with more heavy gold embroidery, and black silk pantaloons. Her face is uncovered, and she is wearing no make-up.

These affluent young Pashtuns seemed as comfortable with their tribal traditions as they were with their “Westernised” urban identities in the photos. They must have felt very optimistic about their future, especially Ariana’s father, a well-paid Russian-educated bureaucrat. “My mother lived like a queen, with many servants,” Ariana tells me. And, indeed, her mother looked like a shy young queen in her wedding photos or at least a teenage princess. Her family was part of a tiny privileged elite in what was then one of the least developed countries in the world. The overwhelming majority of Afghan nationals lived in impoverished rural villages, as they still do, and clung to centuries-old traditions and beliefs, many of which pre-dated Islam. Few villagers were literate. Indeed, Afghanistan’s national literacy rate, at the time, was estimated to be less than ten per cent.

Educated and urbanised Afghans, like Ariana’s parents, were very aware that the feudalism, nepotism, tribalism, piety and ignorance in rural areas was stunting people’s lives and holding back the country’s social and economic development. But what could they do to bring these hyper-conservative rural communities into the twentieth century? What happened over the next decade was a tragedy almost too painful to recount. I tell the story in some detail, however, because it offers so many lessons about exactly what monarchs, governments, politicians and their followers should not do to improve people’s lives and prevent war and conflict, especially at a time when the leaders of the world’s two then-superpowers (the Soviet Union and the United States of America) were aching for another proxy war.

In 1964, King Zahir Shah presented the people of Afghanistan with their first-ever constitution and opened the way for the election of a national parliament.5] The franchise he offered was very limited, however. Just 15 per cent of the population, most of them educated urbanites, would be permitted to vote, and even after the election, King Zahir Shah would remain the country’s absolute monarch.[6] The privileged fifteen per cent nevertheless set about establishing their own political parties, secret societies and study groups with the support of various international sponsors.[7] Some, including members of the royal family, looked to socialism and communism to solve their country’s problems, having been inspired by the stories Indian communists and Soviet advisers, including the ubiquitous KGB agents, told them.

Small groups of intellectuals started meeting in one another’s living rooms to plot Afghanistan’s destiny. Nur Mohammad Taraki, a Pashtun journalist and poet, recruited by the KGB in 1951, chaired one such study group called Khalq, The Masses or The People, after his newspaper of the same name. Another KGB recruit, Babrak Karmal, an ethnic Tajik, chaired a second group called Parcham, The Banner, or Flag.[8] These two Marxist-Leninist factions briefly united to form the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) and, on 1 January 1965, held their first Party Congress in Taraki’s living room. This then-small group of true believers elected a five-member Politburo and a Central Committee, and appointed Nur Mohammad Taraki as its General Secretary, with Karmal as his Deputy. They then set about enlarging their Party’s membership.[9] In the years ahead, these men would wield inordinate political and military power. They would cause the death of thousands of their compatriots and be responsible for the flight of millions of refugees into neighbouring countries.

At the same time, another political movement was emerging in Kabul University’s Theological Department, where academics and students were drawing inspiration from Egypt’s Islamist Muslim Brotherhood. This group wanted to transform Afghanistan into a theocratic state governed in accordance with their narrow interpretations of Sharia Law.[10] They established several political parties, including Hezb-i-Islami Afghanistan (Afghanistan Islamic Party) and the Muslim Youth Organisation, to oppose the King’s democratic modernisation.[11] The Muslim Youth Organisation formally became a political party in 1973 and evolved into Jamiat-i Islami, or the Islamic Society. Among its leaders were men who would also be responsible for the death of thousands of their countryfolk and the flight of millions more as refugees.[12]

The Sixties passed relatively peacefully, despite these conflicting narratives about Afghanistan’s future. The Seventies might have been relatively peaceful, too, had not Nature intervened with the worst drought in living memory.[13] Crops failed, livestock starved, rivers and springs ran dry, and tens of thousands of families left their villages to escape famine. Many crossed the border into Pakistan, a traditional survival strategy in times of crisis, while unknown numbers of those who couldn’t leave died at home of starvation.[14

In Kabul, the famine created political turmoil. In 1973, Sardar Mohammed Daoud Khan, the King’s cousin, brother-in-law, and former Prime Minister, led a bloodless coup d’etat with the support of young military officers, members of the Marxist-Leninist PDPA and other Leftists. The Sardar dissolved parliament, rescinded the constitution, proclaimed a republic, and took up the roles of President and Prime Minister. He was bringing “basic reforms and real democracy” to the people of Afghanistan, he told Kabul Radio listeners in July 1973.[15] King Zahir Shah was in Europe for eye surgery at the time.[16] He didn’t return until 2002.

By the mid-1970s, thousands of dissidents on all sides of the political spectrum had been arrested and imprisoned or executed. Other dissidents, including many Islamists,[17] escaped to neighbouring Pakistan where, under the auspices of Pakistan’s then-President, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, they established bases to continue their struggle against Afghanistan’s new communist Government.[18]

In 1977 President Daoud Khan introduced a new constitution that transformed Afghanistan into a single-party state under his Hizb-Inglabi-Milli, or National Revolutionary Party.[19] By this time, the diverse opposition groups were openly and violently protesting against Daoud’s increasingly repressive policies. The growing Islamist movement had already declared jihad against his regime, and Jamiat-i Islami members were already conducting guerrilla operations against government forces.[20] But the opposition groups were also fighting one another.[21] Hundreds, perhaps thousands of people, were killed in purges and other politically motivated violence. Many thousands more suspected dissidents were arrested by government security forces and imprisoned in already overcrowded jails.

In April 1978, Mir Albar Khyber, a prominent faction leader of the PDPA, was assassinated in an Islamist terrorist attack.[22] His funeral procession became a mass protest against President Daoud Khan’s regime and the increasing US interventions in the region.[23] A week later, the President ordered the arrest of all surviving leaders of the PDPA. Military officers loyal to Nur Muhammad Taraki’s predominantly Pashtun Khalq faction issued counter-orders and launched a coup against the President. They seized all key buildings in Kabul, including the presidential palace and radio stations. Within an hour of the palace falling, Kabul Radio announced, in both Dari and Pashtu, that all power had passed to the Khalq.

President Daoud Khan and most of his family were shot the following day.[24] Daoud’s Deputy, many of his ministers and military officers who remained loyal to him were also killed. Hundreds of civilians, including whole families, were arrested in pre-emptive raids.[25] These horrors are now remembered as the Saur, or April Revolution.[26]

A Revolutionary Council headed by Nur Muhammad Taraki, co-founder of the PDPA and the Party’s first Secretary-General, took control of the new Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. Soon Taraki would also be killed. His name, and his assassin and successor’s, Hafizullah Amin,[27] are burned into the memories of all Kabulis who survived these chaotic years. Including my friend Ariana’s family.

These men, both of them well-educated urbanites—Amin had a Master’s degree in education from New York’s Columbia University, for example[28]—held many of the same values I subscribe to, such as gender equity, equality for all ethnic groups, and universal free education.[29] But such values fundamentally challenged those held by more traditional Afghans, especially in the rural villages and towns. Decrees about women’s rights, including a ban on some of the most degrading and discriminatory customs, such as the sale of girls, for example, not only offended customary law but also challenged what many believed were “the natural liberties of the Afghan male.”[30] The Marxist regime’s campaigns to eliminate feudalism and illiteracy through agrarian land reform and mass education campaigns were equally controversial. When they provoked spontaneous uprisings in villages and towns across the country, the Government responded with brute Stalinist violence and intimidation, which witnesses later described as ‘indiscriminate and disproportionate’ and a crime against humanity.[31]

No one knows to this day how many civilians were killed in military campaigns against rural traditionalists and other counter-revolutionaries. Perhaps the worst atrocity occurred in April 1979 in Kerala, a Pashtun farming village in eastern Kunar Province, where villagers supported Islamist insurgents. One day, after a battle against the Mujahedin, government tanks and armoured personnel carriers surrounded the village and, by some accounts, disgorged two hundred military personnel and several Soviet “advisers”. All the women were ordered into the mosque, all the men into a nearby field. The men were told to kneel and were shot. The death toll was estimated at around 1,170, nearly the entire male population of the village.[32] And then, even while some of the victims were still alive, a bulldozer “began plowing [sic] the bodies into the ground, soft from recent furrowing.”[33]

In 1978/79, Afghanistan’s revolutionary PDPA forces also arrested, imprisoned and “disappeared” tens of thousands of religious leaders, dissident political figures, students, teachers, lawyers, scholars, members of Islamic organisations, and other civilians who opposed the regime.[34 An estimated 12,000 people were executed in Kabul’s infamous Pol-e Charkhi Prison, for example, and in rural areas, up to 100,000 people may have been murdered at this time.[35] Even General Nabi Azami, a member of the Parchami faction of the PDPA and a Deputy Defence Minister after the Saur Revolution, admitted that the revolutionary Government had “arrested too many ordinary people, clergymen, intellectuals” and imprisoned or executed too many “without trial on dark nights and threw them into holes prepared for them.”[36]

Such State terrorism only fuelled armed resistance against the Soviet-supported regime and served the Government’s enemies in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran and the USA.

This was the political environment that my friend Ariana’s parents faced in the first decade of their married life. When they posed for their wedding photos in the 1960s, they could not have known they would be raising their children in a country at war with itself or that they would have to flee Afghanistan for their own survival. Ariana recounts their story while we wait for the Ramazan sun to set. Her younger sister spreads a bright cloth on their living room floor as we talk and places upon it bowls of dates, nuts, fruit salad, deep-fried pakoras, rice, yoghurt, pickles made by an aunt back in Kabul, and stacks of fragrantly fresh Afghan naan, or flatbread. We draw closer to the food as we wait for the television mullahs to announce that yes, at last, we can break the Ramazan fast. Ariana’s mother passes around the dates and other fast-breaking treats.

Traditional Pashtun fare prepared by Ariana’s mother and sister. Photo by Merrill Findlay 2006.

Iftar morphs into a full evening meal: bowls of lamb and vegetable stews, pilau, and yet more warm naan. Ariana’s mother keeps urging me to eat more. She is wearing a navy and white floral shalwar kameez, with a soft white dupatta over her head, not unlike the tulle veil she wore on her wedding day. I glance up at her wedding photos on the shelves. Her face has matured in the three decades since they were taken, yet her face has remained astonishingly untouched by the tragedies she had witnessed and experienced. Like many of Afghanistan’s privileged elite, she and her family continued their charmed existence in Kabul throughout the conflict of the 1970s and ’80s. Her husband used his connections to protect them and ensured that their big house remained a sanctuary from the horrors other Afghans were enduring at this time. Ariana’s birth and babyhood coincided with the assassination of President Daoud Khan, with the excesses of the revolutionary regime which replaced him, and with the Mujahedin’s armed resistance. Then, in the depth of the winter of 1979/80, the Soviet Union’s Red Army invaded.

Planes loaded with Soviet troops and military hardware had been arriving at Kabul’s international airport for days before the armoured military units converged on Tapa-e-Tajbeg, the restored presidential palace. Locals felt the earth tremble as the tanks drove through the city’s streets.[37] Ariana and her older siblings would have heard the first bomb explode at Afghanistan’s central communications hub. Had they been watching from their rooftop, they might also have seen the fires that followed.

That night, five thousand Soviet troops stormed the Tapa-e-Tajbeg palace and killed President Hafizullah Amin.[38] Eyewitnesses reported that they used nerve gas, napalm and incendiary bombs against the Presidential Guards. The gunfire continued all night. By morning all the Afghans who had defended Tapa-e-Tajbeg were dead, their bodies secretly buried on the slopes of the nearby hills.[39] President Amin was replaced by Babrak Karmal, the leader of the Parcham faction of the PDPA.

The Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, and the brutal politics associated with it, led to the deaths of more than a million citizens and at least 15,000 Soviet military personnel.[40] It left thousands of children orphaned in both Afghanistan and the USSR and tens of thousands of people of all ages permanently disabled and psychologically traumatised. It trashed the countryside, reduced agricultural production by two-thirds of the 1978 output,[41] and created the largest refugee exodus since World War II. (Some commentators also claim that the invasion and subsequent occupation accelerated the demise of the Soviet Union itself.[42]) The UNHCR estimated that, even before the Soviet occupation, around 400,000 Afghans had fled into Pakistan and another 200,000 into Iran. [43] From January to December 1980, 80,000 to 90,000 Afghans were crossing the border into Pakistan every month.[44] By the first half of 1981, an estimated 4,700 were crossing the Pakistan border every day, a total of over 140,000 a month.[45]

Ariana’s father was able to support his family by selling hand-woven Türkmen carpets to the Soviet troops as souvenirs, so they remained in Kabul. She, therefore, started school under the Soviet occupation—and here she pauses to convert the year she remembers as 1362 to one which would make more sense for me: 1983. When the last Soviet troops left her country in February 1989, she was entering her teens and dreaming of going to university. But first, she had to finish high school, which is why the family remained in Kabul until after the Soviet withdrawal.

When the Mujahedeen finally entered Kabul in 1992, Ariana’s parents knew it was time to leave. Ariana argued with her father to let her stay to graduate, but one day she saw a schoolgirl like herself being grabbed in the street by bearded men in turbans and bundled into a car. She knew the girl would be punished, or worse, for daring to desire an education. She decided then that it was no longer safe for her to finish high school and reluctantly agreed that, yes, the time had come. Her father hired a couple of buses and drove his family and their possessions, including his carpet collection, to Peshawar. Thousands of other families were also leaving Kabul. The roads were clogged, Ariana recalls. Her homeland was again at war with itself.

I met Ariana in University Town, one of the posher suburbs of Peshawar, where many of the aid organisations had their offices. I was there to see Rabia Ali, the UNHCR’s public relations officer. Rabia was delayed by press interviews about the refugee registration process, so I chatted with the young security staff on duty in the gatehouse while I waited for her. One of the security officers, a proud young Pashtun woman in a regulation blue shalwar kameez and matching dupatta casually draped over the back of her head, wanted to practice her English with me. Her dark eyes and hair highlighted her very fair complexion. She had put a fresh frangipani flower on her desk computer to feminise it and wore pale pink lipstick. Although not a refugee herself, she had Afghan ancestors, she told me. Her mother, a non-literate woman, was raised in a very traditional village and insisted that her daughter be given the educational opportunities she had been denied. This daughter now had a degree in Zoology and Chemistry from Peshawar University and wanted to become a research scientist. She hoped to complete her post-graduate studies in Canada.

Her two male colleagues were also ethnic Pashtuns yet looked very dissimilar. One was fair-skinned, the other dark. Their physical differences demonstrated the diverse genetics of the 52 million people who now claimed Pashtun identity.[46] One of them had studied Sociology and Political Science at Peshawar University and wanted to be a social worker. “But in Britain, not in Pakistan!” he told me. His female colleague joked about how the men in his family insisted that “their” women remained uneducated and wore burkas in public. “We have to follow our traditions,” he said. The young woman laughed. The sooner such traditions died out, the better, as far as she was concerned. “But we’re all Pashtuns!” she quickly added and laughed again, but with a bitter edge. She knew that many of the traditions her colleagues subscribed to suppressed women and girls and nourished the Islamist zealots who threatened anyone who failed to conform to their extremist interpretations of Islam.[47] I understood her desire to study in Canada!

I found Rabia Ali in a spacious office overlooking a lush walled garden in the UNHCR compound. She was dressed in soft pink, with her chiffon dupatta draped over her shoulders rather than covering her hair. Like many young professional women in this city, she wore bejewelled summer sandals smothered in tiny baubles and bows over perfectly pedicured feet. My conversation with Rabia added new dimensions to my evolving understanding of what it was to be young, female and Pashtun in Peshawar in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Yes, Pashtun was her ethnicity, she said, “but call me a Peshawene, a citizen of this ancient city.”

Rabia loved Peshawar: the extraordinary richness of its history, the diversity of its cultural heritage, and its distinctive sophistication, which wasn’t always visible to outsiders like me. Her parents had sent her to one of the city’s best schools, a Catholic college, she told me. “With nuns from Ireland!” Having survived the Irish nuns, she studied English Literature at Peshawar University. She now used her literary skills to promote the UNHCR’s work with Afghan refugees and Pakistanis displaced by natural disasters, Islamist insurgencies, or the Pakistan Army’s military operations. But, on this day, she was so busy juggling media interviews about the refugee registration process she couldn’t leave the office. So would I mind Ariana taking me to the Khurasan refugee camp instead?

The very name Khurasan excited me. It’s derived from the Persian words for “land of the sunrise”[48] because ancient Khurasan, Khorasan or Xorasan, as it is also spelled, was at the eastern rim of the Persian Empire. For centuries, this Greater Khurasan was a centre of Persian and Central Eurasian civilisation, but the name also had more ambiguous, even threatening meanings. For example, it was used in one of Islam’s most controversial and least substantiated hadiths, or traditions of the Prophet Mohammed: “If you see the black banners coming from Khurasan, join that army, even if you have to crawl on ice; no power will be able to stop them …”[49] Islamists, including Islamic State or Daesh, use this hadith to solicit and inspire recruits.

Khurasan has also referred to a variety of other geographies, including the ethnically diverse northern half of Afghanistan beyond the Pashtun homelands,[50] the north-eastern provinces of Iran,[51] a large displaced persons camp and township near the Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif, a high protein heirloom wheat variety,[52] an allegedly al Qaeda affiliated Islamist terrorist group fighting in Syria, (which critics suggest was invented in Washington to justify US interventions in the Syrian conflict),[53] and an Islamic State province,[54] as well as the UNHCR’s refugee camp in the lush Vale of Charsadda, some 35 kilometres from central Peshawar. And Charsadda itself had an ancient and intriguing cultural heritage, as we’ll see.

Greater Khurasan has stretched and withered over the millennia with the changing fortunes of Central Eurasia’s ruling dynasties. One of its defining features has remained relatively stable, however: the Amu Dar’ya. This life-bringing river gushes from the Pamir Knot in eastern Afghanistan to meander across the dry lowlands towards the Aral Sea. The Hellenised Greek speakers of Bactria, a historical region within present-day Afghanistan, knew the Amu Dar’ya as the Oxos, the river Alexander the Great and his army crossed in 329 BCE. Nineteenth-century European travellers, including the young George Nathanial Curzon, who later became Governor-General of India, Latinised the Greek Oxos to the Oxus. This name still appears in many European antiquarian sources.[55]

This Greater Khurasan spans both sides of the Amu Dar’ya to include Afghanistan, eastern Iran, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and south into present-day Pakistan. Historically, it has included the ancient states of Persia, Bactria, Margiana, Sogdia and Khwarazm, the region known as Transoxonia, and the once-great global trading cities of Nishapur, Tus, Herat, Balkh, Kabul, Merv, Samarqand, Khiva and Bukhara, for example. In this extended sense, Greater Khurasan also takes us back through time to the early days of agro-pastoralism and urbanism, to our shared Neolithic sheep and wheat heritage, as recent archaeological excavations in the upper valley of the Amu Dar’ya are revealing. Some six thousand years ago, agro-pastoralists were irrigating wheat and barley crops, grazing sheep, cattle and goats, and living in mud villages in what is now desert in this river valley. Two thousand years later, they lived in cities as sophisticated and advanced as the Bronze Age metropolises of the Nile, Tigris, Euphrates, and Indus River valleys.[56] This “lost” or “forgotten” Central Eurasian society has prosaically been called the Bactro-Margiana-Archaeological Complex, or the Oxus Civilisation.[57] Its recent discovery by archaeologists has forced scholars to rewrite Central Eurasia’s history.

But let’s fast-forward to the last few centuries BCE, when one or more tribes of the steppe confederation we remember as the Yuezhi, or Yüeh-chih, crossed the Amu Dar’ya, to conquer Afghanistan’s Greco-Bactrian kingdoms. Slowly, they transformed themselves from nomadic horse-riding pastoralists into the urbane cosmopolitans remembered today as the Kushans.[58] These steppe pastoralists from Eurasia’s Far East settled down in what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan, adopted (and adapted) the locals’ Greek alphabet and their Graeco-Buddhist and Zoroastrian beliefs, and, in the process, took control of the region’s trade corridors through the mountain passes of the Hindu Kush. Long before the Kushans’ era, these caravan routes, donkey trails and footways had linked the Pacific coasts of China and Southeast Eurasia with the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean with the Black Sea, Caspian, Aral, Baltic and North Seas. Indirect communication between the Roman Empire, India and China’s Han Empire through Khurasan was established by at least the first century BCE, thanks, in part, to the Kushans.[59] This overland trade and communication system is now known as the Silk Road. People have traded, migrated and mixed their genes and memes (ideas) along its maze of crisscrossing byways for tens of thousands of years, as they still do.[60]

Under Kushan hegemony, Greater Khurasan, including Afghanistan, became a regional and global cultural and economic hub and the fountainhead from which memes and genes flowed across the length and breadth of Eurasia.[61] The Kushan aristocracy established their summer capital at Kapisa, near present-day Begram in Afghanistan, the site, in more recent times, of a Soviet and US airbase and an infamous prison. During the winter months, however, the Kushans preferred milder Peshawar, or Purushapura, as it was known, and the Lotus City, Pushkalavati, in the Vale of Charsadda,[62] in what was then known as Gandhara. From these cities, they controlled the north-south trade routes through the mountain passes and the Indus River ports connecting Gandhara with the maritime trade routes of the Indian Ocean.[63]

This constant movement of people, stories, commodities and artifacts left a legacy of extreme cultural and genetic diversity and hybridity,[64] which we can see in the artworks of the era. Here, at the crossroads of global trade, artists and scholars drew on the traditions and knowledge of Indian, Chinese, Persian, Anatolian, Central Asian and Mediterranean civilisations to produce works of extraordinary sophistication and syncretism.[65] For example, Kushan Buddhas wore Greek chitons and Roman togas, and Kushan coins showed the three-faced Hindu deity, Siva, with distinctive Greek, Parthian, and Scythian features.

The era dominated by the Kushans seems like an improbably Golden Age now. The empire probably peaked in the late first or early second century of the Common Era (CE) during the reign of Kanishka I, the “King of Kings” and “Son of God”, as he called himself.[66] It began fracturing in the third century CE after the ruling dynasty was defeated by the armies of the Persian Sassinid empire. But soon, another confederation of nomadic pastoralists rode out of the Central Eurasian steppe to conquer Khurasan: the people remembered today as the Huaona, Hyon, Ye-tai, Hua, Sveta-Hūna, White Huns, Hayathelaites, or Hephthaliti.[67]

Comparatively, little is known about these steppe invaders. Like the Kushans, they settled down, absorbed Khurasan’s syncretic Hellenistic, Indianised and Persianised culture and languages, and selected what suited them from the region’s smorgasbord of belief systems – which, by this time, included Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Hinduism, Shamanism, Christianity and Manichaeism.[68]

In the mid-sixth century CE, a Türkic warrior, Istemi Kaghan, allied with the Persian monarch, Khosraw I to defeat the Hua or Hephthalites. The Amu Dar’ya now marked the border between the Persian and Türkic empires.[69] The conflict between these empires continued for generations,[70] but the Silk Road, with its multiple communication channels, remained open. In 569, the Eastern Roman Empire sent a diplomatic delegation from Constantinople to Khurasan to negotiate direct trade links between Central Asia and the Mediterranean. The Khurasani traders sent them home with a caravan of the best Chinese silk. Many more such caravan trains followed.[71] By the end of the sixth century, Türkic peoples controlled Central Eurasia’s trading routes,[72] while the Persian Sassinids controlled the southern sea routes, including the Indian Ocean trade.[73]

In the seventh century, Khurasan was annexed by General Al-Ahnaf Ibn Qays in the name of Islam’s Umayyad Caliphate. In the following century, another great warrior, Abu Muslim Abd Rahman ibn Muslim Khorasani, or al-Khurasani, led a revolt against the Umayyads from his base in Merv, in what is now Turkmenistan, one of Khurasan’s greatest Silk Road entrepôts. This revolt led to one of the most consequential regime changes in the Muslim world: the transfer of power from the Umayyad dynasty to the Abbasids. Merv became the new ruling dynasty’s first capital.[74]

The merchants of Greater Khurasan prospered under the Abbasid dynasty, even after the second Caliph, al-Mansur, moved his capital from Merv to his brand new City of Peace on the Tigris River, near the ancient town of Baghdad.[75] The abandoned earthen remains of once-great Merv are now inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.[76] Khurasan flourished again in the ninth and tenth centuries CE, under the Persian-speaking Saminid dynasty based in the Silk Road city of Bukhara, in what is now Uzbekistan, and under their successors, the Turkic Ghaznavids. The rise of the Persian-speaking Saminid dynasty coincided with the migration into Khurasan of new waves of Turkic speaking pastoralists from the semi-arid grasslands between the Caspian and Aral seas.[77] The equestrian and archery skills of these steppe warriors were legendary, as was the beauty of their young boys. As a result, thousands of these tribal warriors were employed in the cavalries of the region’s potentates, and thousands of youths were captured as slaves to be sold to Abbasid rulers and trained as personal bodyguards in their palaces.[78]

Slavery was a legitimate business in Khurasan at this time; indeed, the slave markets seem to have underpinned the entire economy. Untold thousands of men, women and children were captured in raids, intertribal wars and dynastic battles to be sold in Khurasan’s markets or sent directly to Baghdad or elsewhere. The Saminid rulers profited by imposing licence fees on the slavers and exacting tolls to cross the Amu Dar’ya.[79] Many of these Turkic slaves reached positions of great authority, wealth and power. Some, like Abu Mansur Sebük-Tegin, even founded rival Turkic empires.

Sebük-Tegin was one of many remarkable rulers of Khurasan. He was captured as a twelve-year-old in Kirgizstan and purchased in Bokhara by the Samani amir’s Turkic Lord Chamberlain, or Commander-in-Chief of the army, Alp-Tegin. Later, still a slave, he became a military commander and accompanied Alp-Tegin to Ghazni, in present-day Afghanistan, where he married his Alp-Tegin’s daughter and, against the odds, established one of Central Eurasia’s most powerful dynasties. The Samani dynasty of Bokhara appointed his son Mahmud as governor of Khurasan. Mahmud annexed Khurasan, and, over the next three decades, extended his family’s empire from present-day Iran to northern India and from the Caspian Sea to the Indian Ocean.[80] Sebük-Tegin and his descendants are now remembered as the Ghaznavids of Ghazni. [81]

Under Ghaznavid patronage, Khurasan produced some of Eurasia’s most influential philosophers, scientists, poets, theologians, and artists, including Abu Ali ibn Sînâ, or Avicenna, whose Canon of Medicine is a founding text of modern European medicine; Abdul Qasim Firdusi, the author of The Shahnameh, which has since become Iran’s national epic and a classic of world literature;[82] Daata Ganj Bakhsh, the Ghazni-born and raised theologian who lived much of his life in Lahore and authored a classic treatise on Sufism, The Unveiling Of The Veiled;[83] and ibn Aḥmad Al-Bīrūnī, the medieval polymath who made profound contributions to early astronomy, mathematics, comparative religion, anthropology, geology and geography. Al-Bīrūnī accompanied Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi on one of his military campaigns into India and produced the first anthropological study of Hindu culture, Ta’rikh al-Hind, or Chronicles of India. He dedicated a later work, his encyclopedia of astronomy, to Mahmud’s son, Mas’ud Ghaznavi.

Like many of his contemporaries, Al-Bīrūnī was a true cosmopolitan. “The ideas and convictions of people show great diversities, and the prosperity of the world rests on such divergences of opinion,” he wrote.[84] He died in Ghazni, Afghanistan, in 1048 CE and is now considered one of the greatest minds of all time.

The brutal stories that Islamist militants tell and enact in Greater Khurasan today would surely bewilder, shock and sadden those very modern Khurasanis of a thousand years ago. The Kushan and Gandahari cosmopolitans of Peshawar (Purushapura) and Pushkalavati would have been similarly dismayed. Yet, their enlightened views still inspire many Afghans and Pakistanis, even in the Khurasan refugee camp. Some 9,000 women, men and children from provinces in northern Afghanistan, the lands of historic Khurasan, were now living in this camp in traditional mud-brick and thatch boxes almost identical to those their Neolithic forebears built 6,000 years ago. Families were each paying the landowner R150 a month rent (around $A1.50) for these basic shelters. In the misery of their daily lives, they were also paying the price of centuries of unconscionably bad governance, tribal violence, political rivalry and neglect in their homeland, and more than thirty years of a proxy war between the world’s two superpowers.

Our little convoy—the white UNHCR SUV and our armed escorts’ Toyota pick-up—was very conspicuous among the donkey carts, motorbikes, jingle trucks, pedestrians and livestock that were also negotiating the camp’s dusty tracks and stinking gutters. Only the Central Business District boasted a sealed road. Here Afghan butchers, grocers, fruiterers, live chicken dealers, timber and firewood merchants, gas suppliers, mobile phone card agents, and a variety of artisans sold their goods and services from rough stalls covered in sheets of corrugated iron or reed-thatch. Other vendors pushed wooden wheeled hand-carts similar to those their ancestors would have made thousands of years ago. The glorious heritage of ancient Khurasan seemed like an improbable fiction that day.

Our little convoy—a white UNHCR SUV and the armed escorts’ Toyota pick-up – was very conspicuous inside the refugee camp. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

We drove on to the Basic Health Unit, a bare concrete block overlooking an irrigation canal. Three Safi Pashtun women in sky-blue burqas were waiting with their children to see the duty nurse when we arrived. They wanted to talk. One woman lifted her burqa and the dark green floral dress she wore beneath it and insisted that I look at a large, suppurating sore on her bare belly. It had begun as a tiny insect bite, she told Ariana, in Pashtu. The bite had become infected and grown into a huge abscess. The nurse explained that she could clean the wound with antiseptics and give the woman antibiotics, but the clinic had no funds to send her to the hospital for the treatment she now required. Again, I felt powerless in the face of the poverty, suffering and courage that confronted me in this twenty-first century Khurasan. And angry, too, that these women’s lives were so little valued that they should be left to suffer in this way.

Open sewers, mudbrick walls in need of repair, roads that turn to mud and slime in wet weather at Khurasan refugee camp. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

Safi Pashtuns were a tiny minority in Khurasan camp. Most of the residents were Afghans of Türcoman, Tajik or Uzbek descent. The majority, some 60 per cent of the total camp population, were Türcoman, descendants of the diverse Turkic speaking peoples who have been mingling their genes in Greater Khurasan for millennia. In the 11th century, their ancestors established the Great Seljuk Empire, which stretched from the Amu Dar’ya to the Tigris River in present-day Iraq. In 1071, one of the Seljuk’s greatest heroes, Alp Arslan, defeated the armies of the Eastern Roman Emperor, Romanos IV Diogenes, at Manzikert, in what is now southeast Turkey, and opened up Anatolia to the Turkic speaking pastoralists of Central Eurasia.[85] Alp Arslan was assassinated on the Amu Dar’ya a year after he and his army defeated the Byzantines. He is revered now as a great ancestral hero. Legends about him still light fires in the bellies of Turkic nationalists on both sides of the Amu Dar’ya. His heirs, and other Turkic steppe pastoralists, established several great empires across the Eurasian landmass. The Safavid, Moghul and Ottoman empires were all founded by Turkic warriors, for example.

In 1221 yet another confederation of steppe nomads crossed the Amu Dar’ya: Genghis Khan’s Mongols. As we’ll see in a later chapter, these warriors conquered all the major Silk Road cities of Greater Khurasan with the rapidity of a sand storm. The richest, most cultured, most learned cities in the world at this time fell like dominoes to these new invaders, and the Silk Road’s camel tracks and footways became escape routes.

Despite the terror and destruction that these invaders unleashed, Genghis Khan and his heirs ensured that the Silk Road remained open for business and that humanity’s genes and memes continued to flow across the entire length and breadth of Eurasia and beyond. This communication network remained open, give or take a few plagues and wars, for another 500 years until the 18th century, when Russian and Chinese Manchu imperialists divided Central Asia between themselves,[86] and British imperialists began intervening from the south. “Turkistan, Afghanistan, Transcaucasia and Persia—to many these words breathe only a sense of utter remoteness or a memory of vicissitudes and of moribund romance,” that George Nathaniel Curzon famously commented after confirming British India’s northwestern borders with Afghanistan. “To me, I confess, they are as pieces on a chess-board upon which is being played out a game for the domination of the world.”[87] His remarks are still prescient.

In 1715 Tsar Peter the Great despatched a military expedition to the Khanate of Khiva on the Amu Dar’ya to establish a Russian base. The wily and brutal Khan won the first round of this unequal contest, but the ineluctable forces of history were not on his side. Over the next 150 years, Russian armies and agents reconnoitred, mapped, invaded, conquered and colonised the tribal lands of Central Asia right up to the border of present-day Afghanistan, in a process that parallels the European invasion, conquest and colonisation of Australia, New Zealand and the Americas. To the imperial Russians, their conquest of Central Asia was a divinely inspired mission to civilise Central Asia’s “half savage nomad population”, as Tsar Alexander II’s foreign minister, Alexander Gorchakov, infamously stated in 1864.[88] However, to the peoples of Central Asia, there was nothing “civilised” about the Russian invasion and colonisation of their homelands. Many of the families at the Khurasan refugee camp were direct descendants of refugees who had crossed the Amu Dar’ya with their livestock to escape Russian domination in past centuries. Ironically, these families had to flee Afghanistan after another Russian invasion by Soviet forces in 1979.

Turcoman mother and her malnourished child at the Khurasan Refugee Camp. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

Although most ethnic Türcomen now live settled or semi-settled lives, they continue to affirm their Türcomanchilik, or sense of who they are as a people,[89] with stories from their pastoral pasts.[90] Since time immemorial Türcomen women have hand-knotted these stories into the designs of the carpets and rugs they made to insulate the floors and walls of their family yurts and covered their wagons.[91] Girls spun wool from family flocks on conical spindle-whorls, dyed the yarn with local herbs, roots and mineral pigments, and spent hours each day at their looms knotting marriage carpets for their trousseaus. It could take up to a year of back-breaking labour to complete a single rug.[92] This ancient tradition continued inside the mud huts at the Khurasan refugee camp. Indeed, some 90 per cent of the camp’s entire population, Türcomen and non-Türcomen adults and children, were now involved in the carpet industry as spinners, weavers, dyers, washers, woodcutters and carriers. But the people who benefitted most from this now-multimillion dollar global carpet industry were the middlemen, the contractors, wholesalers, exporters and retailers in Peshawar and other big cities around the world.[93]

A young carpet maker in Peshawar. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

Ariana and I both had personal interests in Khurasani carpets: Ariana because her father had bought and sold them during the Soviet occupation to support his family, and me because my mother, a farmer and pastoralist in rural Australia, had, for many years, spun the wool from our flocks, dyed it with local plant material, and knitted and crocheted it into heirloom jumpers, jackets and rugs. The scope of the operation I saw at the Khurasan refugee camp made my mum’s efforts seem dilettantish, though!

Ariana led me into a large medieval compound surrounded by high mud walls. At one end, hanks of handspun wool in shades of rusty golds, dark greens, purples and reds were drying on a wood heap near the dying cauldrons. The dark golds resembled the colours my mother achieved with eucalyptus leaves. The Khurasani dyers probably used ground pomegranate skins for these colours and madder root mixed with milk or grape juice for their purples and dark reds.

Bags of dye stuff – herbs, spices, ground pigments – at the Khurasan Carpet Factory. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

At the other end of the compound, under the shade of a rough skillion roof, we saw three four-metre-wide horizontal carpet looms propped up off the dirt floor with bricks. Their frames were strung longitudinally with cotton warp threads, and each carried the beginnings of a plush new carpet. Three artisans were working at one of the looms, two men and a boy. The design they were following, a modern interpretation of a traditional Türcoman carpet, was drawn to scale on a sheet of graph paper: large gold and red squares on a red, green and purple ground. In two weeks, their knees at shoulder height, their heads between their knees as they knotted the wool around the cotton warps, one thread, one knot at a time, the weavers had completed just over one metre of carpet. They still had more than six months of squatting and bending over the loom before they could finish it, painful, back-breaking, exploitative work. The weavers in this sweatshop were on wages of just R2,000, or around $A21 a month. Yet, their completed carpets could sell in New York, London, Paris, Sydney or Berlin for thousands.

Freshly dyed wool drying on the wood heap at the Khurasan Carpet Factory. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

Ariana was concerned about the boy. Children were sexually abused in Khurasan’s carpet workshops, as they were throughout Pakistan and Afghanistan, but no one would admit to it, she told me. This lad, with his sweet smile and adolescent pimples, looked very vulnerable. Ariana asked him how old he was. Fifteen, he said. He looked much younger. Like most of the Khurasan refugees, his family had come from the province of Jowzjan in northern Afghanistan, but he was born in the camp. He’d gone to school until grade 6 and had left six months ago. He’d been working at this carpet factory for one month. His future options were limited, but at least he would now have a skill to earn a living if and when he was repatriated to Afghanistan.

Child carpet worker at the Khurasan camp. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

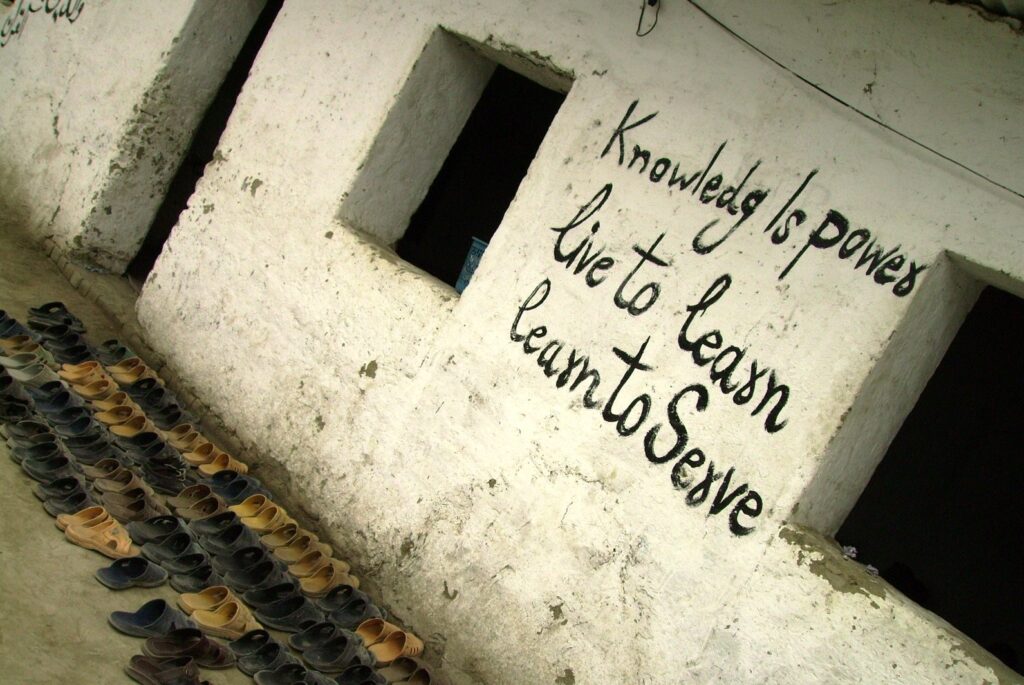

Even this boy’s minimal education gave him six more grades of primary schooling than most kids received. Few families at the camp saw the need for six years of learning. The Deputy Principal of the Khurasan primary school was very aware of this. He had been a journalist in Afghanistan but, like most residents of this refugee settlement, was forced to flee in 1992 when the Mujahedeen were “punishing educated people and Afghanistan was being Islamised,” as he told me. His school was supported by an international non-government agency and an expatriate Türcomen businessman, but his wages were paid by the UNHCR. “We get our salary on time, books are available, we have no problems,” he diplomatically said. His school had very few amenities, though. Through the wooden shutters of the staff room, I could see a dirt courtyard surrounded by white-washed mud-brick classrooms. The windows had no glass, the doorways no doors, the corrugated iron roof no ceiling or insulation. The only fittings in the classrooms were blackboards on the walls and canvas mats on the floors where the children sat cross-legged with their exercise books, boys and girls in separate rooms. The only adornment I could see in this brave little school was a bold black motto, scrawled, in both Dari and English, across one of the courtyard walls: Knowledge [sic] is power/live to learn/learn to serve. English philosopher Francis Bacon made a similar statement in the late sixteenth century.[94] Such words of wisdom have probably been scrawled across school walls in Greater Khurasan for the last thousand years, however.

Graffito on the wall of the Khurasan Camp school. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

Boys and girls had separate class rooms in the refugee camp’s primary school. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

Lessons were taught in Dari and Pashtu and followed Afghanistan education curriculum. Students could also take private classes in English and computer studies. Most of the camp children who were not at school were working in the fields, collecting garbage, making mud bricks, or, like the boy at the loom, weaving carpets to help support their families. The Deputy Principal’s sons had also attended this school and were now studying to become doctors. His older daughter was seeking asylum in Europe but “still living like a refugee”, he told me. Another daughter attended the camp’s self-help community high school, the only option for students whose parents couldn’t afford to send them to private schools. As refugees, they were not allowed to attend Pakistani public schools — unless their families could illegally acquire a national identity card.

I was confronted once again by the human cost of Afghanistan’s decades-long war in another adobe walled fortress compound down the track from the school: a drug rehabilitation centre for female carpet weavers and their children. Opium has been a traditional medicine in Afghanistan for millennia. Carpet weavers frequently use it to help them endure back pain from squatting or sitting at their looms and the long hours of boredom this entailed. Sixty per cent of all opium addicts at Khurasan refugee camp were women,[95] many of them mothers who also used opium to quieten their babies while they worked. They dipped their fingers into their opium pots and let the children suck, which meant that many of the addicts at the centre were also very young children. Typically these kids were expected to work at the loom as soon as they were old enough to tie a knot, but, here, at the rehabilitation centre, they could play in the bare dirt courtyard and go to school away from the threat of opium.

All the women I met at this centre were from villages in northern Afghanistan and generally non-literate and very poor. Many were also single parents. Now, they were gaining new skills, new confidence, new friends, and new support networks while they tried to kick their opium habits. One of their teachers I met was also a young single mum. She taught machine embroidery in a large white-washed room with cheery Chinese mats on the floor. Her students sat on the mats with hand-operated sewing machines learning to zig-zag back and forth across pieces of cotton fabric. This young woman explained that machine embroidery was slow and tedious but much more creative and interesting than carpet weaving and better paid. She was wearing her own handiwork that day, a long green tunic richly machine-embroidered around the neckline and long sleeves. Even though it was now shabby and stained, it was a beautiful example of her craft. She was paid 3,000 Pakistani Rupiah or around 29 Australian dollars a month, the same amount her students earned for a full metre of carpet. She worked far fewer hours and suffered less back pain, though, and could bring her baby to work, a fair-skinned child with big grey eyes. But she couldn’t produce enough milk for her child, she told Ariana and asked if I could give her some money to buy milk powder. Another woman asked for money for medicine. What could I do? Ariana came to my rescue. She explained that if I gave money to one, I’d have to give it to everyone, and I wasn’t rich enough for that. But to the women at this drug rehabilitation centre, I was unimaginably wealthy. I think of them whenever I see an Afghan carpet now, those women and the boy weaving his young life away in that medieval sweatshop.

Refugee children at the Khurasan Drug Rehabilitation Centre. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

What haunts me most, as I write, however, is the bigger picture behind the daily lives of these refugees: the malevolent links between war, arms manufacturers, the exploitation of vulnerable adults and children in the carpet industry, the ongoing impoverishment of their families and communities, and the opium industry. In the year of my visit to the Khurasan refugee camp, opium production soared by 25 per cent in Afghanistan to over 6,000 tons.[96] According to a senior US counternarcotics official, that year’s harvest (2006) was, at the time, “the biggest narco-crop in history”.[97] Terrorist attacks in both Afghanistan and Pakistan also increased dramatically that year, some of them undoubtedly financed with opium money.[98] In 2014, after 13 years of US-led occupation and numerous US-funded eradication campaigns costing nearly 8 billion dollars, opium production in Afghanistan increased by 17 per cent over the previous year’s harvest to an estimated 6,400 tons.[99]

Opium has corrupted every level of society in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as I described in the first chapter. The farmers who grow the poppies, the couriers, truckers, all the small traders who depend on their business, politicians, business people in all industry sectors, the carpet weavers and their families, the millions of opium addicts in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and the fifteen million opiate addicts around the world are all gripped in the deadly embrace with Afghanistan’s Taliban, Pakistan’s ISI, the USA’s CIA, and a host of drug barons, military officers, politicians, warlords, arms dealers, and other war profiteers on both sides of the Durand Line. The opium industry now underpins the entire economy of Afghanistan. This war-ravaged country is addicted to poppies.[100]

But I saw no poppies in the lush farmlands we drove through to and from the Khurasan refugee camp, only fields of irrigated sugar cane, rice, maise and melons, orchards of apples and stone fruit, and some very contented dairy buffalos. For this was the famed Vale of Charsadda, the fecund land watered by the Kabul, Swat and Jindi Rivers, in what was once the state of Gandhara. Somewhere over there, through the sugar cane fields and orchards, were the remains of the great Buddhist city of Pushkalavati, or the City of Lotuses, where, as we’ve already seen, the Kushans established themselves 2,000 years ago.[101] Most of the locals were already Buddhists by the time the Kushans invaded. Indeed, some of Buddhism’s earliest texts were written in the Gandhari language in the monasteries around Pushkalavati and Purushapura.[102] Art treasures recovered from historic Gandhara include some of the first-ever anthropomorphic representations of Lord Buddha.[103

Lush sugar cane fields and a shepherd and his sheep on the road to the refugee camp. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

As we drove back to Peshawar, Ariana told me more about her home city, Kabul, before it was blitzed in 1371, the year I knew as 1992. The year the Soviet-installed regime of President Najibullah collapsed; the year the United Nations failed to negotiate a peaceful transition of power; the year the US government and CIA lost interest because the USSR was no longer a threat; the year the Mujahedin militias took control of Afghanistan; the year Khurasan refugee camp was established; … and the year Ariana and her family joined the mass exodus of refugees from Kabul to Peshawar.[104]

Every kind of atrocity was committed by the warlords and their militias in Kabul that year. Their supplies of military hardware and ammunition seemed inexhaustible.[105] Of Kabul’s estimated population of 1.6 million in 1992, some 700,000 people fled as soon as the shelling began. Of those who remained in the city, 25,000 were killed, according to Red Cross figures.[106] Tens of thousands more civilians were wounded and traumatised in indiscriminate violence and shelling or the crossfire between the warring militias. Untold thousands more people were abducted and “disappeared”. Kabul’s public services were destroyed, including the hospital, which was left with no power or water. The dead were so numerous that bodies were left unburied in the streets. No part of society was innocent in this multi-sided, multi-ethnic tragedy. Every group had blood on its hands. For Kabulis, the wounds have not yet healed.[107]

We turned into Warsak Road and drove through Peshawar’s college precinct beneath a canopy of cooling Australian eucalyptus trees. It was a Friday, and the road was clogged with buses and big cars collecting middle-class students from their private schools. My companion grew wistful as our vehicle crawled past crowds of students in neat uniforms piling into family cars. She recalled her own school days in Kabul, her dreams of going to university. Her memories of the schoolgirl she’d seen being bundled into a car by bearded men in turbans still haunted her. Although Ariana was able to finish high school in Peshawar, university had, so far, eluded her.

All she and her family now had of their former lives were photographs, treasured memorabilia, and memories. Her father had passed away. Her siblings and cousins were now scattered across several continents. And her family’s house in Kabul had been sold to finance two of her older brothers’ travel expenses to Europe. Ariana refused to use the term “people smuggler” because, she insisted, “To Afghans, they are travel agents who save people’s lives and reunite families.” The remittances her brothers now send from Europe pay for their younger siblings’ education.

Ariana herself was as concerned about her family’s present-day lives as she was about their long term future. The Government of Pakistan was determined to send all Afghan refugees still living in Pakistan back to Afghanistan as soon as possible.[108] She knew that if they returned to Kabul, they would face worse conditions than they experienced in exile, and the prognosis for Afghanistan’s future was not good. At the time of my visit, the Taliban had regained control of most rural areas, and security was deteriorating. Militants, including Taliban fighters, aspiring young martyrs from Pakistan’s madrassas, and foreign al Qaeda jihadists, were still crossing the Durand Line from safe havens in Pakistan, often with the support of Pakistan’s army and ISI.[109] Food security was critical. Malnutrition was widespread. And housing, farming land, employment, educational opportunities, and health and medical services were non-existent, unavailable or inaccessible to large population sectors.[110] Conditions in Afghanistan for most people have deteriorated even further since then.

But Pakistan was also very dangerous for Ariana and her family. The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, or Pakistani Taleban, were now targeting civilians all over the country. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the semi-autonomous tribal areas, Mangal Bagh Afridi’s Lashkar-e-Islam and other jihadist groups were assassinating civilians, abducting people for ransom, and conducting suicide attacks on markets and shopping malls. In Khyber, Pakhtunkhwa life was dangerous and uncertain for everyone but more hazardous for refugees because, as a group, they were being scapegoated for all the country’s problems. But Ariana wanted to stay – for deeply personal reasons, as I discovered when I was leaving Peshawar. She visited me at my hotel to say goodbye. She was in love, she confessed. With a Pakistani man. They had been seeing one another secretly for seven years and wanted to marry, but their families refused to give their consent.

On top of everything else my friend had sacrificed, this was too much. Nothing I could say or do could help this young couple. “You can tell my story,” she said, “but don’t use my real name.” I’ve honoured her wish.

I’ve lost contact with Ariana now, and I’m very concerned about her. Has she been deported back to Afghanistan? Has she eloped? Is she in hiding from disapproving relatives or from Pakistani authorities determined to deport all refugees back to Afghanistan? Or has she been injured or killed in a terrorist attack? I don’t know. I do know, however, that since we met, Pakistan has become a much more dangerous place.

“The refugees have become a threat to law and order, security, demography, economy and local culture. Enough is enough,” Pakistan’s Secretary to the Ministry of States and Frontier Regions, Habibullah Khan, told London’s Guardian newspaper in 2012. He had little evidence to support his claim, but his message was clear: “If the international community is so concerned, they should open the doors of their countries to these refugees. Afghans will be more than happy to be absorbed by the developed countries, like western Europe, USA, Canada, Australia.”[111]

Since then, Pakistani authorities have issued more warnings about the imminent deportation of Afghan refugees as illegal aliens, and yet more deadlines have been extended. Few observers believe that the remaining 1.5 million registered Afghan refugees and unknown thousands of unregistered ones still in Pakistan will leave voluntarily, given their fears about what might happen if they are repatriated to their homeland.[112] Few also believe that the thousands of Afghans still fleeing to Europe, North America and, in lesser numbers, to Indonesia in the hope of reaching Australia will subside in the foreseeable future. I hope that Ariana and the man she loves are among the thousands of people now seeking asylum in Germany, where her older siblings live. Wherever they are, may they be safe and happy.

© Merrill Findlay, 2013- 2021

Written in 2013 as part of my PhD project completed through the Centre for Creative and Cultural Research, University of Canberra.

[1] Beloved Kabul, translated by M. I. Negargar, retrieved 9 March 2013, from http://www.farhaddarya.info/translation_beloved_kabul.htm

[2] BBC, 2002, “Operation Anaconda ‘almost over’”, 18 March 2002, retrieved 6 March 2013, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1878224.stm.

[3] AAP, “Afghan-Aussie governor killed,” Sydney Morning Herald, 9 November 2006, http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2006/09/11/1157826844138.html?from=rss.

[4] Arif, A.M. 2006, “Fatal blast rocks Afghan-Australian’s funeral”, Sydney Morning Herald, 12 September 2006, retrieved 21 August 2013, from http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/fatal-blast-rocks-afghan-australians-funeral/2006/09/11/1157826874460.html.

[5] The constitution was drafted by Pashtun and Tajik intellectuals and based on the French constitutional model. It was approved by a loya jirga whose members were hand-picked by the king and his advisers.

[6] Thomas Barfield, Afghanistan: A cultural and political history, Kindle ed. (Princeton University Press, 2010). Kindle Locs. 2707-8; Thomas Ruttig, Islamists, Leftists – and a Void in the Center. Afghanistan’s Political Parties and where they come from (1902-2006), (Kabul: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung: Afghanistan Office, 2006), http://www.kas.de/db_files/dokumente/7_dokument_dok_pdf_9674_2.pdf Pp. 6-10.

[7] Peter Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic terrorism, tribal conflicts, and the failures of great powers, Kindle ed. (2011). Kindle Loc. 2054.

[8] M Hassan Kakar, Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979-1982, In Refugee Research/Afghanistan under author (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). P. 23; Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic terrorism, tribal conflicts, and the failures of great powers. Kindle Loc. 1946.

[9] The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic terrorism, tribal conflicts, and the failures of great powers., Kindle Locs. 2069-70.

[10] Barfield, Afghanistan: A cultural and political history. Kindle Locs. 2708-9.

[11] John Keegan, “The Ordeal of Afghanistan,” Atlantic Monthly, November 1985.

[12] Afghan Justice Project, Casting Shadows: war crimes and crimes against humanity 1978-2001 (Kabul: AJP, 2005).

[13] Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic terrorism, tribal conflicts, and the failures of great powers. Kindle Location 2154.

[14] Fazal-ur-Rahim Marwat, The evolution and growth of communism in Afghanistan (1917-79): an appraisal (Karachi: Royal Book Company, 1997). P. 338.

[15] Ibid. P. 344. This speech was broadcast 17 July, 1973. Barfield, Afghanistan: A cultural and political history. Kindle Locs. 2690-2693.

[16] Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic terrorism, tribal conflicts, and the failures of great powers. Kindle Loc. 2180.

[17] Khawar Hussein, “Pakistan’s Afghanistan Policy” (Masters, 2005), http://www.nps.edu/Academics/Centers/CCC/research/StudentTheses/Hussain05.pdf. P.4.

[18] Frederic Grare and William Maley, The Afghan Refugees in Pakistan, (Washington/Paris: Middle East Institute (MEI), Fondation pour la Recherche Strategique (FRS), 2011), P. 2; Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic terrorism, tribal conflicts, and the failures of great powers. Kindle Loc. 2240.

[19] Marwat, The evolution and growth of communism in Afghanistan (1917-79): an appraisal. P. 350.

[20] Will Davies and Abdullah Shariat, Fighting Masoud’s war (Melbourne: Lothian Books, 2004).

[21] Ibid. Pp. 12-17.

[22] Kakar, Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979-1982. P. 7.

[23] Marwat, The evolution and growth of communism in Afghanistan (1917-79): an appraisal. P. 348, 354.

[24] Ibid. P. 355.

[25] Afghan Justice Project, Casting Shadows: war crimes and crimes against humanity 1978-2001. P. 13.

[26] “Afghanistan The Forgotten War: Human Rights Abuses and Violations of the Laws Of War Since the Soviet Withdrawal,” Patricia Gossman, Asia Watch & Human Rights Watch, last modified February 1991, accessed 10 January 2007. Chapter II, Historical Background. Amin Saikal, Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival (I.B. Tauris, 2006). Ch. 7: Pp. 169-186.

[27] Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic terrorism, tribal conflicts, and the failures of great powers. Kindle Loc. 164; Barfield, Afghanistan: A cultural and political history. Kindle Locs. 2912-13.

[28] Tomsen, The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic terrorism, tribal conflicts, and the failures of great powers. Kindle Locs. 1966-67.

[29] Marwat, The evolution and growth of communism in Afghanistan (1917-79): an appraisal. P. 377.

[30] Ibid. P. 379.

[31] Afghan Justice Project, Casting Shadows: war crimes and crimes against humanity 1978-2001. P. 10.

[32] Edward Girardet, Killing the Cranes: a reporter’s journey through three decades of war in Afghanistan, Kindle Edition ed. (Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2011). Kindle Locations 1821-1926.

[33] Ibid. Kindle Locations 1903-1904; “A grim chapter in Afghanistan war,” Christian Science Monitor, 4 February 1980, http://www.csmonitor.com/1980/0204/020434.html. See Paul Anderson, BBC News, “Calls grow to tackle Afghan war crimes”, 14 February 2005, downloaded 10 March 2013, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/4258343.stm.

[34] Afghan Justice Project, Casting Shadows: war crimes and crimes against humanity 1978-2001. P.12.

[35] Gossman, “Afghanistan The Forgotten War: Human Rights Abuses and Violations of the Laws Of War Since the Soviet Withdrawal.” Ch. II.

[36] General Nabi Azami quoted from his own book on the Saur regime, Urdu and Siasat, or Army and Policy, p. 167, cited in Afghan Justice Project, Casting Shadows: war crimes and crimes against humanity 1978-2001. P. 12. Kronenfeld, “Afghan Refugees in Pakistan: Not All Refugees, Not Always in Pakistan, Not Necessarily Afghan?.” P. 51.

[37] Kakar, Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979-1982. Pp. 8-9.

[38] The Khalk government had Tapa-e-Tajbeg, the presidential palace, restored at a cost of some US $20 million. Ibid. P. 9.

[39] Ibid. P. 10.

[40] The official Soviet figure of 15,000 war dead is disputed. Some commentators put the figure at 50,000. Rafael Reuveny and Aseem Prakash, “The Afghanistan war and the breakdown of the Soviet Union,” Review of International Studies 25(1999).696, footnote 22.

[41] Felbab-Brown, “Kicking the opium habit?: Afghanistan’s drug economy and politics since the 1980s.” P. 129.

[42] Reuveny and Prakash, “The Afghanistan war and the breakdown of the Soviet Union.”

[43] Rupert Coleville, “Afghanistan: the unending crisis. The biggest caseload in the world,” Refugees Magazine, no. 108 (1997)

[44] Grare and Maley, The Afghan Refugees in Pakistan. P. 1.

[45] George Groenewold, Millennium Development Indicators of Education, Employment and Gender Equality of Afghan Refugees in Pakistan: Country Report, (The Hague: Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, 2006), Pp. 2-3.

[46] Rashid, “Pashtuns in Pakistan Speak Out Against the Taliban Insurgency in Afghanistan”.

[47] Ibid. Matt M Matthews, An Ever Present Danger A Concise History of British Military Operations on the North-West Frontier, 1849-1947, Combat Studies Institute Press,US Army Combined Arms Center,Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2010), Pp. 1-2.

[48] See Greater Khorasan, Wikipedia, downloaded 10 March 2013, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greater_Khorasan.

[49] Ali H Soufan, The Black Banners: The Inside Story of 9/11 and the War Against al-Qaeda, Amazon web site (W. W. Norton & Company, 2011). P. xvii.

[50] Anthony Hyman, “Nationalism in Afghanistan,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 34, no. 2 Special Issue: Nationalism and the Colonial Legacy in the Middle East and Central Asia (2002). P. 301.

[51] Pierre Oberling, “Khorasan 1: Ethnic groups,” in Encyclopedia Iranica Online (New York: Columbia University, 2008).

[52] Robert M Quinn, ” Kamut®: Ancient grain, new cereal,” in Perspectives on new crops and new uses, ed. J Janick (Alexandria, VA: ASHS Press, 1999), http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/proceedings1999/pdf/v4-182.pdf

[53] Mark Mazzetti, “A Terror Cell That Avoided the Spotlight,” The New York Times, 25 September 2014 2014, www.nytimes.com/2014/09/25/world/middleeast/khorasan-a-terror-cell-that-avoided-the-spotlight.html. Glenn Greenwald and Mutaza Hussain, “The fake terror threat used to justify bombing Syria,” in The Intercept (First Look Media, 2014).

[54] Bill Roggio, 2015, “Pakistani Taliban confirms death of Khorasan province spokesman, calls for Afghan Taliban and Islamic State to ‘end their dispute’”, Long War Journal, 14 July 2015, downloaded 17 September 2015, from http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/07/pakistani-taliban-confirms-death-of-khorasan-province-spokesman-calls-for-afghan-taliban-and-islamic-state-to-end-their-dispute.php.

[55] Richard Lewington, “The challenge of managing Central Asia’s new borders,” Asian Affairs 41, no. 2 (2010). P. 235.

[56] Nikolaus Boroffka, “Bronze Age Archaeology in Turkmenistan,” News Central Asia (2012), http://newscentralasia.net/2012/01/04/bronze-age-archaeology-in-turkmenistan/ Andrew Lawler, “Central Asia’s Lost Civilization,” Discovery Magazine online 2006.

[57] The ‘Bactro’ in BMAC refers to Bactria, the Greek name of the region around the city of Bactra, or Balkh, in northern Afghanistan, while Margiana refers to the Persian satrapy of Margu, centred on Merv in what is now Turkmenistan.

[58] Xinru Liu, “Migration and settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan: interaction and interdependence of nomadic and sedentary societies,” Journal of World History 12, no. 2 (2001).; “New findings in ancient Afghanistan: the Bactrian documents discovered from the Northern Hindu Kush,” Nicholas Sims-Williams, Digital Archives, Department of Linguistics, University of Tokyo, last, accessed 4 March, http://www.gengo.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~hkum/bactrian.html. Rika Gyselen, ed. Des Indo-Grecs aux Sassanides: données pour l’histoire et la géographie historique, Res Orientales XVII (Groupe pour l’étude de la civilisation du Moyen-Orient, 2007). Osmund Bopearachchi, “Some observations on the chronology of the early Kushans,” in Des Indo-Grecs aux Sassanides: données pour l’histoire et la géographie historique: Res Orientales XVII, ed. Rika Gyselen (Groupe pour l’étude de la civilisation du Moyen-Orient, 2007), http://www.google.co.id/books?id=_TIU_jp93xUC; Peter B Golden, Central Asia in World History (New York: OUP, 2011). Loc. 578-581. Also see “The Kushan Empire (20-280 AD)”, United States Department of Defense US Central Command Cultural Property Training Resource, Colorado State University, downloaded 30 march 2013, from http://www.cemml.colostate.edu/cultural/09476/afgh02-08enl.html.

[59] Matthew P Fitzpatrick, “Provincializing Rome: The Indian Ocean Trade Network and Roman Imperialism,” Journal of World History 22, no. 1 (2011). P. 44-45.

[60] Golden, Central Asia in World History. Loc. 396-397, 424-425; Christopher Beckwirth, Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Asia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Kindle, Amazon Digital Services ed. (Princeton University Press, 2011). Kindle Locs1495-98, 1912-22, 1926-28. D Comas et al., “Admixture, migrations, and dispersals in Central Asia: evidence from maternal DNA lineages,” European Journal of Human Genetics 12, no. 6 (2004). Xinru Liu, The Silk Road in World History, Kindle ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[61] Beckwirth, Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Asia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Kindle Locs 8250-55.

[62] SMEDA NWFP, District Profile: Charsadda, (Peshawar: Small & Medium Enterprises Development Authority (SMEDA), Ministry of Industries and Production, Government of Pakistan, 2009), ; ibid.

[63] Xinru Liu, The Silk Road in World History. Kindle locations 645-651; Nancy Hatch Dupree, Historical Guide to Afghanistan, (Kabul: Afghan Air Authority and Afghan Touist Organisation, 1977). Ch. 3. ADH Bivar, “Kushan Dynasty i: Dynastic History,” Encyclopedia Iranica (2009)

[64] Comas et al., “Admixture, migrations, and dispersals in Central Asia: evidence from maternal DNA lineages.”

[65] Jason Neelis, Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia (Brill, 2010). P. 58.

[66] Golden, Central Asia in World History.Locs.584-585. Tauqeer Ahmad Warraich, “Gandhara: an appraisal of its meanings and history,” Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan 48, no. 1 (2011). P. 14.

[67] Some scholars believe that the English term Hun may be derived from this group’s Persian name. Beckwirth, Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Asia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Locs 2138-2142, 2370-2372; Library of Congress, Afghanistan: a country study (Washington: Claitor’s Publishing Division, , 2001). Pp. 7-8.