The imminent demolition of Quong Lee’s Store represents a failure by local and state government authorities and by community groups to protect local heritage.

… if the Chinese dimensions of our history are erased, if the voices from our Chinese past are silenced, our senses of who we are and who we might yet become will be diminished ….

SUBMISSION TO FORBES SHIRE COUNCIL

about the pasts, presents and possible futures

of an historic building at 161 Rankin Street, Forbes, NSW,

one of Forbes Shire’s last architectural links with our Chinese heritage

and a significant site in the Kate Kelly story,

by Merrill Findlay for The Kate Kelly Project

January 2009 [Last revised 26 May, 2009]

Posted online 14 August 2015.

Update August 2015: The developer who wanted to demolish this building has gone into liquidation, the development application has expired, and the building has been purchased by Bert McNamarra, its former co-owner. So, at least for the time being, Quong Lee’s Store/Beryl & Bert’s Music Store has been saved.

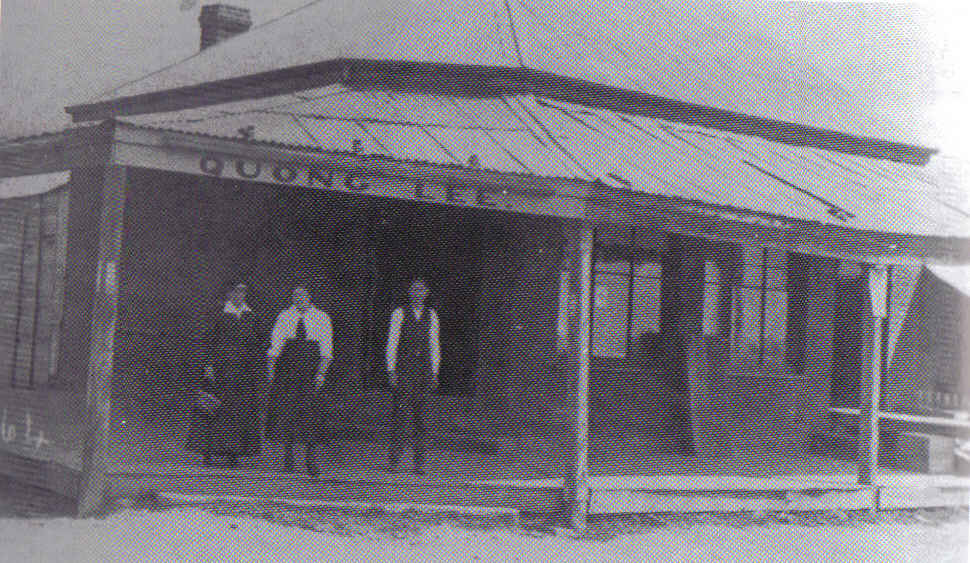

Quong Lee’s Store at the corner of Rankin and Browne Streets in the early C20th, showing Mr Quong Lee with Mrs Margaret Ah Foo, and her daughter. A member of the Foo family also had a dressmaking shop down the road at 96 Rankin Street (Wilton 2004, p. 43). In this photo the side wall facing Rankin Street seems to be boarded up, but the original brickwork shows that the shop once featured two large arched display windows on this side similar to the windows overlooking Browne Street. Photo courtesy Forbes Historical Society.

Quong Lee’s Store aka Beryl & Bert’s Music Store in 2008, at the time Council gave developers permission to demolish it. Photo by Merrill Findlay.

This submission was authored as part of The Kate Kelly Project, in response to a development application for a shopping mall to be built on the block which includes the historic Quong Lee’s Store, also known as Beryl and Bert’s Music Store. It was presented to Forbes Shire Council in January 2009.

Also see RAHS Condemns Quong Lee Demolition Decision >>

And Findlay Wins Medal >>

The Kate Kelly Project (Stage II), is supported by the Regional Arts Fund, an Australian Government initiative supporting the arts in regional and remote Australia, and by other project partners, including Forbes Shire Council.

Stage 1 of the Project (2006-08) was supported by the Royal Australian Historical Society, through a small grant to the Forbes Historical Society, and by other project partners.

© Merrill Findlay 2009

Contents

1.0 Introduction. 7

1.2 What Do We Know About 161 Rankin Street?. 7

1.3 Who was Quong Lee?. 9

1.4 Social significance of Quong Lee’s store. 9

1.5 Connections with Kate Kelly and the Kate Kelly Project 10

2.0 Forbes Shire’s Chinese Heritage: an overview.. 12

2.1 Evidence from burials. 13

2.2.Who were our early Chinese settlers and soujourners?. 14

2.3 Pastoral industry. 15

2.4 Mining industry. 17

2.5 Horticulture and irrigation farming. 18

2.6 Cultural and social life. 20

2.7 The shadow: prejudices and vilification. 23

3.0 Alternative Future For Quong Lee’s Store. 24

3.1 The Vision. 25

3.2 Cultural development opportunities. 26

3.3 Suggested exhibitions and installations. 26

4.0 Recommendations to Council 27

Bibliography. 29

Executive Summary

Archaeologist Dr Ian Jack, President of the Royal Australian Historical Society, inspecting 161 Rankin Street in October 2008. This photo also shows the raised floor level, one of Quong Lee’s vernacular design innovations to ‘flood proof’ the building. The RAHS annual conference in Forbes unanimously carried a resolution recognising the “high historical significance” of Quong Lee’s Store as “the principal item of Chinese heritage in the district’. Photo courtesy RAHS, 2008.

The premises at 161 Rankin Street, Forbes, known as Beryl & Bert’s Music Store, Mathias’s General Merchants and Quong Lee’s Grocery Store, dates from the nineteenth century and is probably the last authentic “physical memory” of the town’s remarkable Chinese heritage. It is also a significant site on the proposed Kate Kelly Trail.

Given the rarity of Chinese heritage buildings in inland New South Wales, this building is historically significant not only to Forbes but to New South Wales and to the nation in general. The Kate Kelly Project urges Council to find ways to retain and restore original sections of it in the proposed Forbes Central development. We also urge Council to undertake a full heritage assessment and, most importantly, an archaeological survey of the site, and to ensure that the photographer who documents the site does so under the guidance of a professional archaeologist and a professional historian to ensure that no details which could reveal important information about the building’s past are missed.

This submission presents Council and AusPacific Property Group, the current owners of 161 Rankin Street, with an overview of the Shire’s Chinese history and outlines the fundamental contributions Chinese migrants and sojourners have made to our pastoral, mining, horticultural, commercial and cultural development over the last 150 years or more. It also offers an alternative vision for 161 Rankin Street, a ‘what might have been’ if Councillors and staff had recognised and acknowledged the site’s heritage significance before approving AusPacific Property Group’s initial Development Application in 2008.

In this alternative vision Quong Lee’s Store is retained, restored to its C19th form, and transformed into a prestigious and vibrant cultural, tourism and educational amenity which draws visitors to the Shire; acknowledges our Chinese pioneers and their legacy; enhances Forbes’s liveability and sustainability profiles; revives ‘forgotten’ dimensions of our local and family histories; enriches and deepens local people’s sense of place and cultural identity; and presents new opportunities to revive Chinese traditions which were once celebrated in Forbes, including Chinese New Year.

The first Chinese people to arrive in what is now Forbes Shire may have come with the early ‘squatters’ as shepherds or servants from the late 1840s. The gold rushes of the 1860s brought hundreds more Chinese migrants who worked as miners, merchants and market gardeners, and in many other capacities. Early records of burials show that Chinese people were on the Forbes goldfields from at least 1863. Many Chinese people established long-lasting businesses in the Shire, including general stores, such as Quong Lee’s, restaurants, and many market gardens along the lagoon and river. Chinese horticulturalists, such as William Ah Foo, were irrigation pioneers and innovators in intensive food production. They employed many people, both Chinese and non-Chinese, and by the early twentieth century were producing vegetables for the entire region. By the 1880s more Chinese people were probably living on pastoral stations and in bush camps than in town, however. Hundreds of Chinese men were employed to clear land, excavate dams, fence, shear, and to do other station work, including cooking and gardening, at this time. Many of the farms in the Shire were first cleared by contracted Chinese work gangs.

The Kate Kelly Project offers this overview of the Shire’s Chinese heritage in the hope that Councillors, Council staff and the new owners of 161 Rankin Street will never again be able to plead ignorance of the heritage significance of Quong Lee’s Store, or dismiss the legacy left by the hundreds of Chinese pioneers who helped to make the Shire what it is today. We also offer an alternative future for the building in the hope that it will inspire Council to think more holistically and creatively about the Shire’s future cultural, social, economic and environmental needs.

Forbes, NSW, January 2009

1.0 Introduction

The shop on the corner of Rankin and Browne Streets, once known as Quong Lee’s Grocery Store, dates from the second half of the nineteenth century when Forbes Shire was home to a substantial Chinese community. That this building may also be the last remaining Chinese-built structure in the Shire greatly enhances its heritage status. The old store is also a significant site on the proposed Kate Kelly Trail.

Despite the building’s undeniable heritage significance, Forbes Shire Council approved a Development Application (No. 2008/0101) for a shopping centre and car park on the block bounded by Rankin, Lawler, Riley and Browne Streets at a Special Meeting on 1 August 2008. By approving this development Council formally authorised the demolition of Quong Lee’s Store.

As this submission will show, Quong Lee’s Store could be much more valuable to Forbes Shire if it is retained and restored than if it is demolished to make way for a few extra car parking spaces. The Kate Kelly Project, in consultation with other groups, including Forbes & District Historical Society and the Royal Australian Historical Society, offers this ‘alternative vision of the future’ for 161 Rankin Street in which the old store is retained, restored and transformed it into a prestigious cultural amenity and tourist asset.

We also present an overview of the Shire’s Chinese heritage to ensure that it is never again ‘forgotten’ or overlooked in Council decision-making processes. We do this in the hope that efforts will now be made to publicly acknowledge and celebrate the contributions made to the Shire’s development by hundreds of Chinese-born migrants in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and to appreciate the many contributions that Chinese and other migrants are continuing to make in the Shire in the twenty-first century.

1.2 What Do We Know About 161 Rankin Street?

The historic building at 161 Rankin Street, now Beryl and Bert’s Music Store, was known as Mathiases’ General Merchants from the early twentieth century and, before that, as Quong Lee’s Grocery Shop. The Mathias family has probably been associated with the premises since the second decade of the twentieth century when May and Steve Mathias leased it from a Mr Gaymard to establish their own business, Mathias’s General Merchants, sometime after 1914, the year the couple married. May Mathias sold groceries, hardware, chaff and hay from the building (McLean 2003; McNamara 1997).

According to Mathias family lore, the shop was built by Quong Lee “after a very high flood in the 1800s” (McNamara 1997, p. 638). The lot is on the floodplain so would have been inundated during floods, but a number of vernacular innovations, including the height of the floor above ground level, suggest that Quong Lee may have designed the shop to be ‘flood proof’. Its position at the corner of Rankin and Browne Street would have been extremely favourable in the nineteenth century, notwithstanding the threat of inundation. It was very close to the South Lead goldfield so would have attracted pedestrian and other traffic to and from the mines on what are now the netball courts and Halpins Flat; and it was on the route to the market gardens on what was then called the Condobolin road (a continuation of Browne Lane/Street) and to the stations, farms and settlements further west, including Bedgerebong, Yarrabandai and Condobolin. These factors suggest that the existing corner store may have been built on the site of an older premises, or that it represents a reconstruction of an existing shop which may have been damaged in a flood. The history of the site can only be confirmed by an archaeological survey and possible excavation, accompanied by further documentary research, including a title search, however.

In an interview with members of Council’s Heritage Advisory Council in 2003, one of May and Steve Mathias’s children, David Mathias, who grew up at 161 Rankin Street and lived for many years next door at No. 5 Brown Street, confirmed that the building was “a Chinaman’s shop” before his family acquired it. He recalled “a big Chinese garden” and seeing the Chinese “opening big tins of ham” to eat, which suggests that Chinese people may have been living in the vicinity during his childhood. (Dave Mathias was born in 1914.) He also recalled family stories about a “Chinese gambling den” across the road near his father’s timber yard on Rankin Street, but admitted that this was “before my time” (McLean 2003). Another local informant, Esme Smith, one of many descendants of William Ah Foo who arrived in Forbes during the mining era, also recalls family stories about the building’s Chinese provenance and confirms that a Mr Lee “had a Chinese grocery shop” there (Smith 1997). Members of the Foo family also operated a corner store and other businesses in Forbes.

The Mathiases purchased 161 Rankin Street from a Mr Gaymard, who had apparently bought it from Mr Quong Lee. Mary and Steve Mathias owned the building until 1966 when one of their daughters, Beryl Mathias, acquired it with her husband, Bert McNamarra. The Mathiases were accomplished musicians and keen performers, and sold and maintained musical instruments in their general store. It was a natural progression, therefore, for ‘Beryl and Bert’ to transform the business into a music shop (McNamara 1997, p. 638). This building’s Mathias era is also worth exploring further.

Dave Mathias recalled that, in his childhood, 161 Rankin Street had 13 rooms, including a very large room that was used for public events, and a row of rooms on the western side which his mother rented out as single men’s accommodation. These rooms are now remembered as The Bushman’s Home (Toole and Toole 1997, p. 292; McLean 2003; McNamara 1997, p. 637). Dave also recalled windlasses operating at South Lead and briars covering Halpins Flat (McLean 2003).

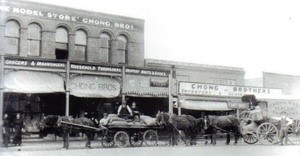

There were several other Chinese general stores in Forbes during Quong Lee’s era, including the very large Chong Brothers Model Store in Rankin Street but, although some of the bricks, mortar and timber may remain from these establishments, they do not retain the architectural integrity or historical authenticity of 161 Rankin Street. The uniqueness of this building is one of its key values. Further investigations, including a land titles search and archaeological survey, will reveal its history in greater detail.

1.3 Who was Quong Lee?

Very little is known about Mr Quong Lee, the proprietor of 161 Rankin Street from the late C19th to the early C20th. Esme Smith remembers a Sam Quong Lee, who may have been the same person or a close relation (Smith 1997).[1] An undated photo of 161 Rankin Street, which was possibly taken in the early twentieth century, shows Quong Lee with two of Esme Smith’s relatives, Margaret Ah Foo and her daughter. Quong Lee appears as a tall, slim, well dressed man in waist coat and shirt sleeves, but it is impossible to determine his age from the photograph.

An 1893 newspaper report also refers to a shopkeeper called Peter Ah Lee (Forbes & Parkes Gazette 1893). So was Peter Ah Lee associated with Quong Lee and his shop? Or were there several unrelated merchants called ‘Lee’ in Forbes at this time? With the limited information currently available it is impossible to answer these questions.

We do know, however, that most of the Chinese who arrived in Australia during or after the gold rushes of the 1850s and ‘60s were Cantonese speakers from Kwangtung (Guongdong) in the Pearl River Delta in southern China (Wilton 2004, p. 41; Williams 1999, p.11). It is probable, therefore, that Quong Lee also came from this region. Many Chinese migrants at this time were non-literate but, given his business success, we can assume that Quong Lee was literate, at least in Cantonese and possibly in Mandarin Chinese, if not in English. He may also have been considered a community leader. As such, he would have been called upon to write letters to families back in China on behalf of his non-literate customers and friends, and read the replies; to help the Chinese community with migration issues, such as filling in application forms for Certificates of Exemption from the Dictation Test, and to act as translator and ‘go-between’ in their dealings with colonial institutions and the broader community (Wilton 2004, pp. 40-41); and to send remittances back to China for his customers. He may have headed a local ‘tong’ or hui-kuan (a ‘same-place’ society)[2] or been a member of a Chinese Masonic Lodge (Fitzgerald 2004). Like many other Chinese migrants, he may also have had a wife and family back in China whom he supported and visited from time to time, or a Chinese or non-Chinese partner in Forbes (Halles 2004).

1.4 Social significance of Quong Lee’s store

Forbes’s largest C20th Chinese-owned shop, Chong Brothers Model Store, in Rankin Street, c. 1900. The signage boasts that it sold groceries, ironmongery, household furnishings, drapery, boots and shoes. In the 1880s the premises was owned by the Prow family and known as Prow & Son’s General Store (Mathews 1885). Photo courtesy Forbes Historical Society

Although we know little about Quong Lee himself, it is certain that his shop and the goods and services he and his staff sold were of vital importance to the hundreds of predominantly single Chinese men who lived and worked within what is now the Shire of Forbes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. His shop would have been a meeting place for the local Chinese community, especially for the many market gardeners along what is now the Bedgerebong Road, and the hundreds of Chinese ring-barkers, scrub clearers, dam builders, fencers, shearers and other pastoral workers who only came to town occasionally. But, given his shop’s strategic position, his customers may also have included many non-Chinese people, including pastoralists, selectors, miners, rural workers and townsfolk.

Eliza Ah Duck, the young English wife of 28 year old market gardener, Jimmy Ah Duck, reported seeing some fifteen Chinese men in animated conversation in a Chinese shop she claimed belonged to her husband’s cousin, Peter Ah Lee, in November 1893, an observation which confirms the importance of such stores to the Chinese community as meeting places, social centres and refuges (Forbes & Parkes Gazette 1893). Eliza Ah Duck’s comments also suggest that in Forbes, as in other inland towns, many of the Chinese settlers and sojourners were closely related or were born in the same villages.

The Shire’s earliest Chinese stores were probably simple canvas tents and rough slab huts hastily erected in the early 1860s from which traders could sell food and manufactured goods to the diggers. The proprietors of these stores would have filled their shelves with imported goods, including traditional Chinese foods and medicines, and with whatever fresh produce was available. They probably also sold opium, which could be legally imported until the early twentieth century (Wilton 2004, p. 17). The storekeepers may also have offered a range of services, including transmitting customers’ remittances to their families back in China (Williams 1999, p.22). Many merchants also sponsored relatives from their home villages to Australia and provided them with employment, board and lodgings. Some employed Chinese cooks to prepare fresh noodles and other traditional fare for their staff and to sell, as well as Chinese carpenters to manufacture household goods to order (Wilton 2004, p. 3) Quong Lee might also have extended his business in such ways. His shop would therefore have been a node in a global network linking Forbes with Sydney, Hong Kong and China (Wilton 2004, p. 47).

Henry Lawson’s oft-quoted short story, The Ghosts of Many Christmases, reminds us that the Chinese stores also served the broader non-Chinese community. In this story Lawson recalls Sun Ton Lee & Co’s store at Gulgong where there were “strange, delicious sweets that melted in our mouths, and rum toys and Chinese dolls for the children” – and where “Santa Claus was a Chinaman” (Lawson 2009). Forbes children may have experienced similar thrills at Quong Lee’s. This shop may therefore have been an important institution not only to the Shire’s Chinese residents but to non-Chinese people too. Quong Lee’s life and the story of his shop are worthy of much more investigation and interpretation.

1.5 Connections with Kate Kelly and the Kate Kelly Project

An intriguing photo of uncertain provenance from the Mathias Collection labelled ‘Kate Kelly’s House’. We can only speculate now about where or what this ‘house’ was. One suggestion is that it was an old miner’s shack on Lawler Street behind the Foster’s family home at No. 1 Browne Street. Kate Kelly is also reported to have lived in other places, however. At the time of her disappearance she may have been living as a single parent with her children, including a baby, at the corner of Browne and Sherriff Streets (Forbes and Parkes Gazette 1898).

Photo courtesy Forbes & District Historical Society.

As well as embodying our Chinese heritage, No. 161 Rankin Street is also associated with Kate Kelly, the sister of bushranger Ned, who arrived in the district in the mid-1880s. Kate Kelly initially worked at Cadow Station on the western rim of the Shire, then owned by the Jones family. She moved to town in about 1886 and worked in several households in Lachlan and Rankin Streets. In 1888 she married William Henry Foster, better known as ‘Bricky’ (1867-1946), the son of Quong Lee’s neighbours, Mary and Frederick Foster, who lived at No. 1 Browne Street (where MacFeeters’ wool store now stands).

When she decided to marry Bricky Foster, Kate Kelly was working as a ‘home-help’ for the Prow family in their private residence in Lachlan Street (Foster 1955). The Prow brothers then owned a large department store on Rankin Street which they later sold to the Chong Brothers who developed it as one of the largest Chinese stores in the region. Kate and Bricky Foster may have lived at or near No.1 Browne Street during part of their married life, but we have no verifiable evidence of this.

Kate Kelly and the Foster family would almost certainly have shopped at Quong Lee’s, however. Kate Kelly probably also passed the store, perhaps even stopped for a chat with Quong Lee and his staff, on 5 October, 1898, the last day she was seen alive. Her decomposing body was found in the lagoon at the back of Ah Toy’s market garden near Chinaman’s Bridge, on what is now the Bedgerebong Road (an extension of Browne Street). Local police recovered the body from the lagoon and brought it to Mrs Ryans Carlton Hotel diagonally opposite Quong Lee’s Store on the corner of Rankin and Browne Streets where the Video-Ezy store now stands. The body was examined by the local doctor and formally identified, and taken from the hotel to the Forbes cemetery for burial the following day (Forbes and Parkes Gazette 1898).[3] One can only imagine the conversations which must have taken place across the street at Quong Lee’s Store at the Foster family home at this time.

The Foster family arrived in Forbes during the gold era in the 1860s and may have lived at No. 1 Browne Street from that time. Bricky Foster and his eleven siblings were all born at this address; his father, a mining prospector, died there in 1908;[4] and members of the family continued to live on the site until at least the late 1940s. Bricky’s mother, Mary Foster, signed the house over to her bachelor son, Arthur, or Artie Foster, a Sunday School teacher, in 1929, as documentation held by Forbes Museum shows. Bricky Foster spent the last decades of his life in a house or hut behind the Mathiases. He died in the Forbes hospital in 1946 at the age of 80, and is buried in the Forbes cemetery some distance from his wife.[5]

Dave Mathias left many anecdotes about Brickie Foster and his brother Artie, both of whom he knew personally, and about Kate Kelly (McLean 2003). He remembered an image above Bricky Foster’s fireplace showing Kate Kelly on horseback after she won the jumps at Wagga Wagga Show, for example. He also recalls how his father, Steve Mathias, laid water on to Mr Foster’s residence and helped him plough up a large vegetable garden (McLean 2003). Dave Mathias’s relationship with the Foster family was such that he inherited all their memorabilia relating to Kate Kelly and her children. Dave’s nephew, Robert Reid, is now the custodian of this historically valuable but still-uncatalogued collection.

The Chinese dimensions of the Kate Kelly legend continue even beyond her death, since her body was found in the lagoon at the back of Ah Toy’s market garden near Chinaman’s Bridge. Little is known about Ah Toy himself, however. A single line in the Forbes Court House records for a 14 year old child named George Clifford Ah Toy, who died on 10 April 1880 (Forbes Family History Group 2003, p. 41), suggests that Ah Toy may have had a family, and perhaps even, like many Chinese men, an Australian-born wife (Bagnall 2006). Ah Toy almost certainly would have been a regular at Quong Lee’s store and, given the migration patterns of the time, he may also have been related to the store’s proprietor, or been born in the same village.

Kate Kelly herself would have grown up knowing Chinese merchants, diggers, market gardeners, tobacco farmers, shearers and agricultural workers in northeastern Victoria, probably including some of the ‘old timers’ who had been the victims of the anti-Chinese riots on the Ovens Diggings in 1853 (McQuilton 1979, p. 14). She may even have spoken a little Cantonese which she could have learned from her Chinese acquaintances, or from her one-time boyfriend, Aaron Sherritt, or from their mutual friend Joe Byrne, a member of the Kelly Gang, who grew up on a small selection near a Chinese settlement in the Woolshed Valley near Beechworth. Joe Byrne was so comfortable with Chinese settlers that he was known as Ah Joe by his Cantonese mates (Corfield 2003, pp. 7, 83). Joe Byrne, Aaron Sherritt and Ned Kelly himself were all charged with assaulting Chinese men, but their apologists are quick to point out that these attacks were driven by “youthful ‘hot-headedness’” and an inability (or unwillingness) to resolve conflicts peacefully, rather than by racism and xenophobia (Ian Jones 1992, Friendship That Destroyed: Ned Kelly, Joe Byrne and Aaron Sherritt, cited in Frost 2002).

A number of Chinese migrants also worked as police agents and informers in Northeastern Victoria but some, like Ah Ping and Ah Soon from the Upper King River, were clearly Kelly Gang sympathisers. A Chinese merchant on the Buckland River may also have supplied the Gang with provisions while they were on the run (McQuilton 1979, p. 62, 145; Corfield 2003; O’Lincoln 2006, p. 104). Other Chinese traders may have supplied the Kelly Gang with the fireworks that were used allegedly as signals during the Siege of Glenrowan in 1880. A Constable James Arthur claimed that he saw Ned Kelly leave the Glenrowan Hotel soon after two rockets exploded in the sky. Other witnesses confirmed that the rockets may have been signals and that they saw Ned addressing an estimated 150 armed supporters while the police were still besieging the hotel. Evidence has since emerged that Ned Kelly and his supporters may have been about to proclaim a Republic in Northeastern Victoria and that the fireworks may have been associated with this plot (Phillips 2003). Ned Kelly returned to the hotel – and the rest is history!

These stories have no direct bearing on the Kate Kelly Legend as it is narrated in Forbes, although they add depth and colour to it. They also confirm the relevance of Chinese settlers to the Kate Kelly Project.

2.0 Forbes Shire’s Chinese Heritage: an overview

Even though there are few remaining ‘material memories’ of the Shire’s Chinese heritage, many older residents can still remember buying vegetables from Chinese market gardeners, and even enjoying Chinese New Year and other traditional celebrations as guests of the Ah Foo family, who had a market garden on the Forbes lagoon, or George Wing or George Hing Lee, who farmed at Horseshoe Bend on the Lachlan and at other sites around Forbes (Glanville 2003), for example. Stories also survive about the close relationships between Chinese and non-Chinese people in the Shire, including a number of marriages between Chinese-born men and Australian or British-born women. Sadly there are also stories about racially motivated violence, xenophobia and racial vilification, especially in the decades leading up to Federation and the introduction of the White Australia Policy, which are also part of our shared heritage.

Many local farming families also remember Chinese cooks and gardeners who worked on the pastoral stations, and can recall stories about the Chinese work gangs who excavated many of the dams in the district and ring-barked and cleared much of the land that was later opened up to selection or acquired for soldier settlement blocks. Artifacts from this era can still be found, including camp sites with the remains of clay ovens; fern-like Chinese ‘Angel trees’ which still grow and sucker in many old gardens; and opium poppies which still appear each year to mark the passing of the men who planted the first seeds.

2.1 Evidence from burials

Other towns and villages in the Central West, including Parkes, Bogan Gate and Condobolin, still have recognisably Chinese graves in their cemeteries which remind locals of their Chinese heritage. This is not so in Forbes, even though dozens, possibly even hundreds of people of Chinese descent have died in the Shire over the last 150 years or more. Unfortunately none of the undertakers’ records have survived for the Forbes cemetery from before 1913, and nor do any of the Chinese grave markers remain, possibly because they were burned in a bushfire which apparently swept through the cemetery and destroyed “anything that wasn’t masonry” at this time.[6] Jean Glanville, who grew up on market gardens in Forbes in the 1930s, claims that the town’s Chinese residents were still being buried at the Forbes cemetery well into the twentieth century, however. She remembers that the graves of three Chinese men who died on one of the Forbes market gardens were “dug up and sent back to China in containers”, for example. This exhumation was accompanied by traditional Chinese rites, including offerings of roast duck, pork and whisky, and the burning of incense, cigarettes and money in two kerosene tins beside the graves. Some of the food was ritually set aside in bowls for the ancestors, as tradition demanded, but the rest was consumed at the grave side as a funerary feast (Glanville 2003).

Forbes Shire Council’s earliest cemetery maps and burial records, which were acquired from the undertakers Morris Brothers, make no reference to Chinese burials in the Forbes cemetery, and nor do they show a Chinese section where such rituals might have taken place. Yet it is clear from the death and burial records held at the Forbes Court House that dozens of people with identifiably Chinese names have been buried in Forbes and the surrounding districts since 1863 (Forbes Family History Group 2003).

A quick look of the ‘A’ sections of the Forbes Court House death and burial records transcribed by the Forbes Family History Group reveals the following identifiably Chinese names of people who were buried in and around Forbes: Ah Ching, died 14.11.1881, aged 43 years, Forbes; Tommy Ah Choy, d. 20.6.1908, 58 yrs, Forbes; Jimmy Ah Chung, d. 15.12.1897, 50 yrs, Forbes; Ah Cop, d. 1.6.1871, Forbes; Charlie Ah Cow, d. 14..11.1896, 59 yrs, Forbes; Jimmy Ah Duck, d. 7.11.1893, 28 yrs, Forbes; Ah Duk, d. 28.9.1892, 44 yrs, Forbes; Jimmy Ah Foo, d. 13.4.1897, 60 yrs, Moobong; William Ah Foo, d. 12.07.1880, Forbes; Ah Fook, d. 31.12.1899, 56 yrs, Forbes; Ah Go, d. 26.12.1885, 52 yrs, Forbes; Ah Gue, d. 16.3.1889, 27 yrs, Forbes; Ah How, d. 24.1.1870, 37 yrs, Lachlan River; Ah Pin, d. 17.7.1879, 35 yrs; Ah Ping, d. 20.5.1864, Forbes; Ah Pow, d. 22.12.1894, 62 yrs, Forbes; Ah Sam, d. 28.3.1863, 25 yrs, Forbes; Ah Siang, d. 28.8.1863, about 30 yrs, Forbes; Ah Sundee, d.7.2.1866, 41 yrs, Forbes; George Clifford Ah Toy, d. 10.4.1880, 14 yrs 9 mnths, Forbes; Ah Van, d. 25.111882, 60 yrs, Forbes; Ah Sam, d.26.9.1875, 50 yrs, Bogabigal; Ah Sam, d. 13.12.1875, 30 yrs, Marsden; Ah Toon, d. 8.8.1888, 26 yrs, Oakhurst near Forbes (Forbes Family History Group 2003, pp. 13 & 41).[7] So where are the graves of all these people?

It is certainly possible that remains from a number of the Forbes graves were exhumed and returned to China for reburial, as Jean Glanville describes in her memoir, and as occurred in Parkes and other cemeteries in New South Wales. At Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney, for example, “an average of 75% of Chinese burials were removed to China between 1875 and 1930” (Williams 1999, p.49). It is probable that many Chinese burials still remain in the Forbes cemetery, however, and that a ‘non-consecrated’ part of the cemetery was set aside for Chinese and other non-Christian burials. According to folk memory some of the Chinese graves may have been located along the Edwards Street boundary of the Forbes cemetery, but none of the surviving records show graves in this area, according the Council Staff. These ‘lost’ burials could possibly be ‘rediscovered’ by conducting an archaeological survey of the oldest parts of the cemetery using remote sensing technology.

Records of 48 Chinese burials dating from 1873 to 1945 have survived in neighbouring Parkes and have provided intriguing information about that town’s Chinese community. Nineteen of these records show the deceaseds’ occupations, for example, including a “baker (or perhaps builder), boarding house, cook, doctor (3), gardener (6), green grocer, grocer, hawker, labourer, miner, publican and shoemaker” (Yvonne Hutton 1998, List of Chinese names from Parkes and Goobang cemetery records, Parkes Historical Society, cited in Wilton 2004, p. 41). Such records in Forbes, had they survived, might have shown an even greater diversity of occupations. In both Parkes and Condobolin the Chinese grave sites have been restored, and a traditional burning tower has been rebuilt in Condobolin. Similar respect might, one day, be paid to the Chinese who are buried in Forbes cemetery—once their grave sites have been re-discovered.

2.2.Who were our early Chinese settlers and sojourners?

Many locals assume that Chinese people first came to Forbes during the gold rush era but it is possible that Chinese shepherds, servants and cooks were in the district earlier than this. The links between China and the colony of New South Wales date from 1788 when some of the ships of the First Fleet sailed on to Canton to re-load after delivering their cargos of convicts to Sydney Cove. Many of the ships on the Sydney route were also crewed by Chinese sailors and may have carried Chinese passengers who settled in the colony. One such settler, Mak Sai Ying, also known as John Shying, had established himself as farmer in the colony from 1818, for example, and by 1829 was the publican of The Lion hotel in Parramatta. In the 1820s three Chinese men were also employed on properties owned by the Macarthur family; and from the late 1840s more than three thousand indentured laborers were shipped from China to the colony of New South Wales as cheap labour for the pastoral industry (Darnell 2004; Williams 1999, p. 40). It is possible that some of these men and boys also found their way down the Lachlan with the early squatters.

The gold rushes of the 1850s and ‘60s brought thousands more Chinese-born people to the colonies. Ann Curthoys claims that “by April 1861 there were almost 13,000 Chinese living and working in New South Wales” making up “about a quarter of all miners in the colony” (Curthoys 2001, p. 106). In Australia as a whole at this time, some 38,000 people, or 3.3 per cent of the non-indigenous population, were born in China. An estimated 40 percent of the Chinese who were in New South Wales in the 1870s and 1880s had migrated from Chung Shan (Zhongshan) in southern Guangdong (Kwangtung), while the rest of the Cantonese speakers came from Ko Yiu (Gaoyao), Tung Gwun (Dongguan), Toi Shan (Taishan) and San Wui (Sunwei) districts of Guangdong. Some ethnic Hakka people also migrated to New South Wales from non-Cantonese speaking districts in Zhongshan (demographer Charles Price cited in Wilton 2004, p. 47). Many of these men would have migrated together in groups from the same villages, and/or their migration would have been sponsored by relatives already in Australia. They would all have spoken with distinctive local accents which would have enabled other Cantonese and Hakka speakers to tell where they came from (Williams 1999, p.11).

Most of these migrants were “young, single men escaping wars, famine, feuding or being shanghaied into service,” according to a descendant, Fleur Fallon, whose great-great grandfather, Qi Ya Mei, sailed from Hong Kong to Melbourne in1853, at the peak of the Taiping Rebellion in southern China, to try his luck on the goldfields. Qi Ya Mei was literate in Mandarin, which suggests that he was from a well-to-do family. Like other Chinese migrants he was expected to send regular remittances home and to “return to marry a Chinese woman and take care of [his] ageing parents” (Fallon 2008). Many of these migrants did return to China, but others, including Qi Ya Mei it seems, settled in Australia.

We don’t know how many Chinese came to the Lachlan goldfields in the1860s, but if they followed patterns documented in other parts of New South Wales, a majority of those who arrived at this time and chose to stay in the colony may have settled in or around Forbes to establish businesses and/or work as traders, horticulturalists, domestic servants, station hands, gardeners, cooks, sheep washers, shearers, carters and seasonal labourers, for example (Curthoys 2001, pp.115-116). These migrants may also have included Chinese doctors and herbalists like Charlie Chong and Lei Bing Hing who treated both Chinese and non-Chinese patients in Dubbo into the twentieth century (Wilton 2004, p. 38).

The Chinese community would have been a relatively cohesive group in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Webb and Enstice 1998), even though many of their Australian-born children, including the descendants of William and Margaret Ah Foo (Smith 1997), for example, married into non-Chinese families. As a group they would have been considered “an integral part of the social, cultural and economic life of the district” (Reeves 2004, p. 176). As Michael Williams emphasises in his thematic history of Chinese settlement, “By Federation, Chinese people in NSW were a significant group, running numerous stores … societies and several Chinese language newspapers. They were also part of an international community involved in political events in China such as sending delegates to a Peking Parliament or making donations at times of natural disaster” (Williams 1999, p.6). In Forbes, at this time, Chinese people were similarly engaged in diverse activities with local, national and international dimensions.

2.3 Pastoral industry

Station homestead shaded by a mature ‘Angel Tree’ planted by a Chinese gardener in the late C19th. The gardener also maintained the station vegetable garden growing both traditional Chinese and European greens. Some of the dams on this station, Boorathumble near Euabalong on the Lower Lachlan, were excavated by hand by Chinese work gangs. Photo from the Findlay family collection.

In 1848 120 men and boys were shipped from the port of Amoy, or Xiamen, in China’s Fujian Province, to Sydney, as cheap labour for the Australian Agricultural Company and other colonial pastoral interests. Over the next four years more than three thousand indentured laborers were sent from Xiamen in what was known as the ‘Chinese Coolie Trade’ to work in rural Australia (Choi1975, cited in State Records NSW 2003; Northrup 1995, pp 56-58; Darnell 2004). A number of these migrant workers made their way across the Blue Mountains to Bathurst (Darnell 2004) so it is possible that some of these men were employed as shepherds or servants by the early squatters on their runs along the Lachlan River.

The ‘Coolie Trade’ ceased in 1852/53 after unscrupulous practices by the British companies, Tait and Co. and Syme, Muir and Co. and their Chinese brokers and agents, provoked riots in Xiamen (Northrup 1995, pp 56-58). The gold rushes of the 1850s and ‘60s brought thousands more Chinese to the colonies, many of whom found work in the pastoral industry after the gold rush era, especially from the late ‘60s when investment in wool production increased. The pastoralists considered Chinese workers much more reliable than other groups at this time because they were not “given to getting on the spree”, as the manager of a Riverina station commented (Wilton 2004, p. 33).

From the 1860s the colony governments passed a number of Land Acts to reduce the influence of the ‘squatters’ and to ‘throw open’ their pastoral runs to free selection by a new generation of aspiring farmers. The pastoralists did everything possible to deter the selectors and, from the 1880s, won the right to claim ring-barking of trees as improvements for which they could expect compensation (Frost 2002, p. 121). Ringbarking also significantly increasing stocking rates, as the manager of Coan Downs, north of Hillston, observed in 1890 (McGowan 2005). Hundreds of thousands of acres in southeastern Australia were ring-barked by Chinese work gangs from this time. In 1886 the Edols of Burrawang Station, on the western rim of Forbes Shire, for example, hired Chinese gangs to ring-bark some 50,000 acres for “1/9 per acre” (Judson c. 1976, p. 8, 11). Chinese work gangs may also have dug channels on Burrawang to drain the wetlands along Gunningbland and Goobang Creeks (Edols, 1957, in Judson c. 1976, p.11), and excavated a number of dams on the station, including one near Ootha. Land clearance and earthworks on this scale would have been impossible at this time without Chinese labour.

Chinese ring-barkers and scrub cutters were employed by Chinese contractors and lived in large camps on the stations or on the fringes of towns. Their food, tools, transport and other services were supplied by local Chinese merchants and entrepreneurs, possibly including Quong Lee in Forbes. Many of these bush communities also included skilled irrigation farmers who produced fresh vegetables for the workers and, in many cases, also supplied neighbouring homesteads and settlements. A Chinese garden near Euabalong, which may have been associated with a large ring-barking camp, is known to have also had “at least one joss house”, which indicates that the bush workers continued their religious practices while they were clearing the land. (McGowan 2005).Such was the scale of these operations that the number of Chinese men living in the bush around Forbes at this time may have exceeded the number living in the town.

A government report based on field research undertaken in 1883 by the NSW Sub-Inspector of Police with Chinese businessman Quong Tart gives us a glimpse of life in such settlements. At Narrandera, for example, a large camp was established on leased land:

There were 340 people at the camp, of whom 12 were gardeners, 124 were labourers, and 64 were cooks, store keepers, owners of gambling or opium houses and other related occupations.. At some periods the population was much larger when the men returned from their contract work on the pastoral properties. The camp was surrounded by a palisade, outside of which were an orchard and several hectares of vegetables (McGowan 2005).

Provisions for this camp were supplied by local businessman Sam Yet, who also employed some of the ring-barkers and brush cutters in the district. One of his work gangs cleared 24,300 hectares on Moombooldool for “one shilling an acre” (Wilton p. 33), for example.

Seeds from Chinese opium poppies still grow wild on many farms and along the road verges around Forbes. Photo by Merrill Findlay,

Many farming families within Forbes Shire, especially those on farms that were once part of Big Barrawong and other large stations, have inherited family stories about the Chinese work gangs. Some of these locals have even found evidence of Chinese occupation, such as old camp sites with clay ovens, or patches of naturalised opium poppies. Older people can also remember the last Chinese station gardeners who “produced nearly all the vegetables in the bush” and “could turn their hand to rabbiting” and any other “rough work” which was required of them (McGowan 2005). By the 1890s Chinese men were also working as wool washers and scourers, carters and shearers in the pastoral industry (Wilton 2004, p. 3, 41). Chinese cooks were also catering for thousands of people in inland New South Wales at this time. The Census of 1891 enumerated 849 Chinese cooks in the colony who represented “about half the cooks in country hotels and about a quarter of those in private homesteads.” In the following decade, when the pastoral industry was in decline and unions were campaigning against Chinese workers, the number of Chinese cooks dropped to 535 and kept falling over the following decades (Wilton 2004, p. 37).

Forbes writer, Paul Wenz, has left us with a moving description of a station cook from this era, a fictional character called Ah Sin who could “serve up mutton, with inexhaustible variety, twenty one times a week”. Ah Sin, who is undoubtedly based on someone Wenz knew, was a “coolie” from Canton who migrated to New South Wales in search of gold. He wore his “pigtail”, or queue, rolled “around his shaven skull” and, at sixty years of age, had just one desire: “to go and die in China and be buried in the land of his ancestors” (Wenz 2004, pp.7-8). Hundreds of Chinese men working in the pastoral industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would have shared this wish. Some of them fulfilled it, but many others didn’t, as the records of deaths and burials in Forbes and elsewhere in rural New South Wales confirm.

Of all the Chinese pastoral workers the shearers have the most poignant history. They worked in the sheds for many years with non-Chinese shearers and were members of early trade unions, but from 1888 were excluded from joining the emerging the Amalgamated Shearers Union. Throughout the strikes of the following decade Chinese shearers were accused of being ‘scabs’ or ‘strike breakers’. Banjo Patteron’s ballad, A Bush Song, records the conflict of this era: I asked a bloke for shearing once, down on the Marthaguy,/ ‘we shear non-union here’, he said,/ ‘I’ll leave you then’ said I,/ I looked along the shearing shed,/ before I turned to go –/ There were four and twenty Chinamen/ a-shearing in a row (quoted in Wilton 2004, p. 35).

It is possible that the Forbes Chinese community may also have been caught up in the conflict between unionists, non-unionists and pastoralists at this time. According to an undated and unattributed document in the Forbes Family History Group archives, there were “altercations between shearers and Chinese” near Chinaman’s Bridge on the Bedgerebong Road which, the author notes, “did not help racial tension in the town at the time” (Forbes Family History Group, Undated). Such a statement begs clarification and further explanation—but that must await further research.

The contributions made by these bush workers and contractors when Australia was still “riding on the sheep’s back” remain under-appreciated and under-acknowledged. As Barry McGowan observes, “Their perseverance and success surely earns them the long-denied accolade of pioneer” (McGowan 2005). [8] Some of these men are celebrated with a range of Riverina wines made by the descendants of Italian migrants who wanted “to pay recognition to those early Chinese scrub cutters and ring barkers”. Their Scrubcutter Old Vine Wine is now served in Chinese restaurants throughout NSW. As the promotional material claims

The Chinese played an intrinsic role in the clearing of the rugged Australian Bush. Chinese market gardeners and ringbarkers were essential in opening up the new frontier ahead of early farming settlers. Their tenacious work ethic and ability to succeed in those harsh early conditions was widely respected by other pioneering settlers, and has become the stuff of legend in the long history of Outback Australia.

In the main, the important role the Chinese have played in the shaping of Australia and their place in history has often been overlooked.

2.4 Mining industry

Gold was discovered near Bathurst in 1851 when, as the Bathurst Free Press reported, “A complete mental madness appears to have seized almost every member of the community. There has been a universal rush to the diggings.”[9] Almost decade later, in 1860, alluvial gold was found in Burrangong Creek at Lambing Flats (Young) and, the following year, at Black Ridge, the present-day site of Forbes.

In the decade between the Bathurst and Forbes strikes some 500,000 people migrated to the Australian colonies, including more than 38,000 Chinese, most of whom were from southern China. Some of the 3,000 indentured labourers ‘imported’ as cheap labour for the pastoral industry may also have “absconded” to join the gold rush (Curthoys 2001, p. 105). Most of the new arrivals arrived on a “credit ticket” system:

They were organised into groups of between 30 and 100 men, connected to one another by kinship and locality, under the supervisions of a leader of some wealth. Their kinship connections meant they could develop strong group cohesiveness and purpose, attributes which allowed them to survive difficult times much better than many other groups of diggers (Curthoys 2001, p. 105).

On several goldfields Euro-diggers reacted violently to the presence of the Chinese. European mobs infamously attacked the Chinese camps at Lambing Flats on at least six occasions in 1861 (Mo Xiangyi and Wang Jingwen 2009), for example. On 14 July of that year police finally read the Riot Act, an event which is now re-enacted during Young’s annual Lambing Flat Festival, as “a poignant reminder of the need for understanding and acceptance of cultural diversity.”[10]

On Christmas Eve of that same year, 1861, a digger on the Lachlan goldfield, Harry Stephen or ‘German Harry’, struck a layer of gold bearing gravel at the bottom on his shaft near the present-day intersection of Lawler and Grenfell Streets, Forbes. Within months an estimated 30,000 miners rushed to the new diggings. The Gold Commissioner actively discouraged Chinese from entering the new Lachlan goldfields to prevent a repetition of the Lambing Flats violence. In 1863, however, after the easy gold was mined out and the population crashed to just 3,000, Chinese and European diggers urged authorities to allow the Chinese onto the Forbes fields. Burial records show that they were already in Forbes from 1863, even though the Lachlan goldfields weren’t formally opened to them until February the following year (Curthoys 2001, p. 116). Even though many of the Chinese diggers were still under contract to the entrepreneurs who brought them to the colony, they worked cooperatively with the Euro-miners (Williams 1999, p.47). The relationship between the two groups seems to have been relatively peaceful in Forbes.

In the decade after 1861 the Chinese population of New South Wales halved “from more than 14,000 to a little over 7,000” (Curthoys 2001, p. 115). We don’t know how many Chinese people remained in Forbes, but some 80 percent of those who were on the Lachlan goldfields from the 1860s could have remained in the district as traders, horticulturalists, herbalists, traditional doctors, hawkers, domestic servants, station hands, gardeners, cooks, sheep washers, shearers, carters, and as seasonal labourers (Curthoys 2001, pp 115-116). Many Chinese also bought land, established market gardens and other businesses, including general stores like Quong Lee’s, and contributed to the development of the Shire in countless other ways.

2.5 Horticulture and irrigation farming

A large proportion of Cantonese speakers who migrated to the Australian goldfields in the C19th were from rural areas of Southern China and brought with them thousands of years of inherited knowledge and experience in intensive irrigation agriculture and horticulture. Many of these settlers put their ancestral knowledge into practice as soon as they found land to cultivate and reliable sources of water. In Forbes, Chinese farmers may have been growing vegetables and fruit along the Lachlan River and beside the lagoon from the early 1860s.

Nineteenth century observers tells us that, by the 1860s, Chinese market gardeners had established themselves in nearly all settlements in the colonies of New South Wales and Victoria: there was “scarcely a town but is now well supplied with all kinds of household vegetables by these celestial gardeners”, one commentator reported from Victoria in 1863 (McGowan 2005). Some of the early Chinese horticulturalists leased their blocks, but others probably purchased their own small farms. Chinese farmers are known to have taken up selections of around 20 acres under the new Land Acts in the 1860s in North Eastern Victoria, for example (McQuilton 1979, p. 45-46), and may have done so in the Forbes district from this time. Further evidence for Chinese market gardening during the gold rush era comes from early maps of the Araluen goldfields in southern NSW, which show that Chinese farmers were leasing land soon after gold was discovered. The remains of two such irrigated gardens near the village of Jembaicumbene can still be seen. Another Chinese market garden assemblage at nearby Glendaurel Station, which includes a dam, water race, piping, irrigation channels, mounds and old fruit trees, gives us insights into some of the technologies Chinese horticulturalists were using at this time.

In 1864 four Chinese men were regularly seen “carrying thousands of buckets of water from a local lagoon each day” to irrigate their crops on a vegetable farm at Deniliquin (Curthoys 2001, pp115-116). Evidence of early Chinese irrigation can also be found at the site of a former ring-barking camp near Rankin Springs, where gardeners drew water from a “collared well built over a spring” and constructed channels and embankments to irrigate their crops. The remains of at least two huts and what may have been a blacksmith’s forge have also survived at this site, which suggests that the Chinese may have been making and/or repairing their own tools and possibly even designing their own horticultural equipment at this time (McGowan 2005). A Chinese farm on the Murrumbidgee River at Darlington Point, which was described by contemporary sources as a “spectacular success”, was “watered by two wells, and traversed throughout by canals” (McGowan 2005). By the 1880s irrigation seems to have become partly mechanised on such market gardens. Chinese farmers at Hillston, for example, were hauling water from the Lachlan in buckets “which were fastened to an endless chain driven by one horse going round and round continuously”. The buckets tipped the water into canals or into ponds “of about 1350 litres capacity” from which water was carted by hand in large watering cans attached to shoulder yokes. Such irrigation methods were apparently similar to those used in China, Korea and Japan in the early C20th (McGowan 2005).

Remains from another market garden at Major’s Creek include “several small round pits, which may have served as repositories for night soil” (McGowan 2005). ‘Night soil’, or human excrement, was a traditional Chinese fertiliser, of course, and there is anecdotal evidence that it was used on Forbes market gardens until at least the 1930s, or until artificial urea and other fertilisers were available: “Men piddled into buckets, which were tipped into a pond, then diluted with water, then put into watering cans and used on vegetables, particularly lettuce,” Jean Glanville, who grew up on three different market gardens around Forbes, recalls. She also notes that the urine was mixed with horse and cow manure “in a big cement pond with water”. Later, when commercial urea was available, the human urine was omitted from these home-brews (Glanville 2003).

In other parts of NSW Chinese farmers also grew tobacco, corn and broom millet. Locals from around Tumut can remember the Chinese irrigating tobacco and other crops by carrying “nine to eighteen litre cans of water on a yoke [and] watering their plants with a long handled home-made dipper or ladle” in the first decades of the twentieth century, for example. These farmers also roasted their tobacco and employed non-Chinese labour to cut and carry timber for their kilns. Chinese farmers are known to have grown tobacco at Black Range near Albury from the 1870s to the 1890s, in Inverell to the 1930s, and “on the river flats near Dubbo and on the Macquarie Flats at Bathurst” (Wilton 2004, p. 30). They may also have grown tobacco around Forbes.

Chinaman’s Bridge on the Bedgerebong Road, Forbes, NSW, near the site of several Chinese horticultural blocks. Photo by Merrill Findlay, 2006.

Although little evidence of the presence of Chinese horticulturalists has been preserved in the Forbes Shire, it is well known that there were many market gardens along the river and “along the edge of the lake” near Chinaman’s Bridge in the nineteenth century (Huthnance Undated). William Ah Foo bought a small block on the lagoon in 1883, for example: “This was approximately two acres and over the next few years gradually built up to the twelve acres that remain in the family to this day” (Smith 1997).

Other market gardeners from this era include Ah Toy, whose garden was on the lagoon near Chinaman’s Bridge (Forbes and Parkes Gazette 1898), and Jimmy Ah Duck, who rented “a portion of Mr G Heinke’s garden at Willodene, near the weir” at South Forbes (Forbes and Parkes Gazette 1893; Forbes and Parkes Gazette 1893). Chinese horticulturalists who were still producing vegetables in the twentieth century include George Hing Lee, who had a river block at Horseshoe Bend in the 1930s; Sing Lee who owned a property on the Grenfell Road at this time; and George Wing who was initially Hing Lee’s partner and later established a large market garden on “98 acres of virgin land” on the river (Glanville 2003).

George Wing migrated from Southern China in the twentieth century and worked for some time at the Shanghai Café in Campbell Street, Sydney, before moving to Forbes as George Hing Lee’s business partner. Jean Glanville recalls that Hing Lee employed “five or six Chinese men” and a number of non-Chinese labourers at the time and delivered fruit and vegetables around town by truck. After several years George Wing bought George Hing Lee’s block and employed eight of his Chinese workers, including “Willie the Cook”, who had previously worked in a Parkes hotel (Glanville 2003). George Wing sold this block soon after he bought it because “the land was played out” (it had been producing vegetables “for 40-50 years”) and went into partnership with Clarrie Wyatt, a bachelor who ran cattle on a block on the Grenfell Road near Forbes. George installed irrigation plant and constructed canals to produce beetroot, carrots, parsnips, cabbage, cauliflower, French beans, tomatoes, pumpkin, watermelon, cucumber and lettuce which he delivered to green grocers in Cowra, Young, Grenfell, Orange, Parkes Condobolin and probably Forbes, in a “a five ton Fargo truck, forest green with ‘George Wing, Market Gardens, Grenfell Road, Forbes’ painted in gold on the side.” He employed both Chinese and non-Chinese workers, including Alf Khan, who was of mixed Aboriginal and Indian or Afghan descent (probably ethnic Pathan). Many of these men lived on the property in “huts made of galvanized iron or wooden slabs” with “dirt floors” (Glanville 2003).

Jean Glanville remembers many of the workers individually, especially “Willie the Cook”, who had a small private garden in which he grew traditional medicinal herbs and Chinese vegetables. Each month he “would go into town with the horse and cart to deliver vegetables to the Globe Hotel and get supplies for the market garden.” The publican would give him a “few whiskies”, according to Mrs Glanville, and “late in the afternoon they would carry him out, place him in the back of the cart… untie the horse, give it a whack on the rear, and the horse would find its own way back to the garden.” Jean Glanville also recounts how the Chinese men would “squat on the ground” with water pipes made from lengths of bamboo, and quietly smoke their tobacco and drink tea: “A large teapot, with a cane handle, was filled with Chinese tea, and placed in a wicker basket, about a foot round and padded inside, to keep it warm. Trays with small handle-less cups, upside down. During a break they would have a cup of tea and a couple of puffs on the pipe, which was then passed around among the men” (Glanville 2003).

Agricultural scientist Ted Henzell claims that “ Chinese market gardeners set the standard for vegetable growing in Australia for a long time after the end of their involvement in gold mining” (Henzell 2007, p. 241). In Forbes, as elsewhere, their skills “in crop selection and planning, labour management and marketing of their produce” allowed them to successfully produce a wide range of European and Asian vegetables and fruit, even in harsh conditions. They innovated by growing sensitive crops between rows of sweet corn to protect them from frost and wind (Frost 2002, p. 124), by utilising storm water and soakages in ways that “would appear to have been foreign to most European gardeners” (McGowan 2005), and by adapting traditional methods of fertilizing their crops to suit local conditions. By the 1880s Chinese market gardeners had become “specialists in labour-intensive farming” throughout the Australian colonies (Frost 2002, p 119). What they achieved in the face of extraordinary challenges in Forbes and elsewhere in rural New South Wales leaves us “an excellent and persuasive example of environmental and technological adaptation” (McGowan 2005) that we can still learn from and be inspired by.

2.6 Cultural and social life

It is difficult to imagine today what life was like for Chinese migrants when they first arrived on the Lachlan goldfields in the 1860s: few of them spoke English; they looked very different from other diggers; they had left behind everything they were familiar with; and almost all of them were unaccompanied males whose primary concern was to make enough money to pay off their debts and to send some back to their families in China. What they brought with them, however, were generations of cultural traditions which they were soon sharing with non-Chinese diggers. Town and Country Journal reported in 1870, for example, that, in the gold town of Sofala, “terrestrials and celestials appear to hob-nob together with that degree of intimacy which naturally comes of long acquaintance.” (Town and Country Journal, 30 July 1870, cited in Curthoys 2001, p. 118). This same “degree of intimacy” may also have been evident in Forbes at this time.

Chinese New Year gave the Shire’s Chinese-born residents, such as horticulturalists William Ah Foo and George Wing, and possibly Quong Lee, an opportunity to share their traditions with the broader community. Past and present Forbes locals of both Chinese and non-Chinese descent can still remember celebrating Chinese New Year with fireworks, moon cakes and gifts of little red envelopes stuffed with money. Esme Smith recalls stories about the Foo family’s hospitality in the twentieth century, for example, when “birthday celebrations would mean a chef from Sydney, a week’s festivities and fireworks” (Smith 1997); and Shirley Hansen recalls her mother telling her about celebrations in Forbes “when Chinese from all around the area would attend the banquets which lasted for days” and “lucky red packages would be handed out to all the guests” (Wilton 2004, p.98). According to Shirley Hansen, these festivities also included ‘Double Tenth’, a holiday commemorating the Wuchang Uprising of 10 October 1911 and the fall of China’s feudal Quing dynasty. Forbes people may therefore have been celebrating Chinese festivals and other cultural traditions for at least eighty years, from the 1860s to the 1940s.

Jean Glanille fondly remembers Chinese New Year celebrations on George Wing’s market gardens in the 1930s:[11]

… a couple of weeks beforehand there was much excitement, and a big order was sent to Sun Quong Hing’s, Chinese importers [in] Campbell Street, Sydney. Special Chinese cakes, several different varieties, were ordered. Some looked like English pork pies, with pastry on the outside, and a filling of fruit mince. Others had egg yolk in the middle, or what I think was a thick custard with fruit, mostly dried fruit. This firm also supplied long-grain rice from China in large bags, stone jars of preserved ginger in syrup, packets of preserved ginger, Chinese herbs and spices, dried mushrooms (from China), Chinese whisky, Chinese tea, and boxes of Chinese sausage (Lup Cheong) etc. An invoice or delivery docket would be sent advising the expected date of delivery of the goods. They would be delivered by train to the Forbes railway station, and we would collect in the truck, George Wing driving, as none of the (Chinese) men had licenses.

The night itself would be a big party, set out throughout the house and once in a marquee. The meal would comprise roast duck, roast pork, roast chicken, big bowls of steamed rice, and lots of vegetables. The ducks took about three days to prepare – we had guinea fowls and ducks at the garden (no chooks) and the ducks would be killed by breaking their necks, then the throat would be slit, and the blood drained into a container and used in some of the food. Then the feathers were removed by plunging the bird into boiling water in a galvanized bath tub, which loosened up the feathers, and made them easier to pluck. Then the innards would be removed: some parts were given to the dogs, others like the livers and hearts were a delicacy and used in cooking. The ducks were rubbed down with oil, then George made a hole in the skin of the duck and inserted a straw and blew into it. This lifted the skin, and created a crispy skin during cooking. The ducks were then put onto a spit and suspended over a coal fire and turned regularly, cooking for several hours. Pork was bought locally and done the same way, prepared 3-4 days beforehand with soy sauce and various herbs and spices, then oiled and placed on a spit. Chickens were mainly steamed, cut up and put on platters with vegetables. Lup Cheong had to be heated, then sliced up.

Vegetables served during the dinner included Chinese cabbage, Chinese radishes, carrots, (no potatoes, parsnips or pumpkins are used in Chinese food) asparagus, dried Chinese mushrooms, (fresh mushrooms were available, but not used in Chinese food) celery, Chinese pea, rather like a snow pea. Vegetables were always steamed, with the exception of mushrooms. These were soaked in boiling water for a few hours, then placed with other vegies.

Plates of cakes were then put on the table; there was no dessert as such. Fireworks were used occasionally at first, but banned, after my dress got burned, and Stella’s black umbrella was ruined by errant crackers. At Hing Lee’s and Sing Lee’s places, the drinks served were beer, Chinese rice wine, whisky and Chinese whisky, spirits and ordinary wine, and soft drinks. But at Wyatt’s there was no rice wine or Chinese Whisky; George Wing loved ordinary whisky, Stella the beer .…

People sat around afterwards talking, there was no singing or music, and no games. The evening started about 7 or 7.30, smorgasbord type arrangement on long trestles, and lasted ’til 2-3 in the morning. No equivalent to Auld Lang Syne; no midnight countdown, etc. There were no special costumes, the Chinese workers dressed in their usual clothes, which were fold-over trousers, very wide at waist, folded from one side to other, then tied round waist with sash. Their jackets were high collar, with splits up the side (Glanville 2004).

Chinese New Year is still celebrated privately in Forbes, of course. Forbes Chinese restaurateurs decorate their restaurants with traditional red and gold Good Luck banners and celebrate the beginning of a new lunar year, but it is many years since we have seen celebrations on the scale of those hosted by William Ah Foo and George Wing’s on their horticultural properties.

Other than the annual New Year celebrations the main recreational activities enjoyed by the early Forbes Chinese community seem to have been socialising with friends over tea and listening to music. Travelling troupes of Chinese Opera and acrobatic performers may have visited the Shire from the 1860s, although no direct evidence of this has emerged so far. Traditional Chinese musical and theatrical performances are known to have attracted large audiences on the Victorian goldfields in the 1850s, and at a Chinese camp at Cooktown in Queensland in 1877, however (Williams 1999, p.51); and a Chinese opera company performed at Tingha in New South Wales during “the hey days” (Wilton 2004, p. 57), which probably means during the 1870s tin boom. It is therefore possible that Chinese performers also visited Forbes.

Many Chinese migrants also played and enjoyed western-style music, of course: businessman Quong Tart is famously remembered for performing Scottish airs on the piano and reciting Robbie Burns poems on the diggings at Braidwood, for example, and clarinettist Louis Lupp, “whose father was born in China about 1844”, was the bandmaster of the Bathurst City Model Band in the late nineteenth century (Wilton 2004, p. 58). Given the Shire’s rich multicultural heritage from the gold rush era, it is likely that such cultural fusion was also taking place in Forbes.

Opium smoking was also a recreational activity for both Chinese and non-Chinese people in Forbes in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century. An estimated one third of Chinese men in rural NSW smoked opium at this time, either as a recreational drug or as a drug of dependence. But other members of the Chinese community, such as Quong Tart in Sydney, campaigned against drug use. Opium could, nevertheless, be imported legally until 1906 and was a valuable source of revenue for colonial governments (Williams 1999, p. 70). Opium was also available as Laudanum and as an ingredient in other popular medicines and tonics. Quong Lee and other Chinese traders in Forbes may have legally supplied opium products over the counter as a normal part of their business.

Gambling may have been a much more widely practiced recreational activity than opium smoking, however. Card games, dominos, horse racing, Fantan (now played on gaming tables in casinos), and Pakapoo, “a form of lottery based originally on 80 Chinese characters and … thought to be the basis of Keno” (Williams 1999, p.53), may all have been popular in the C19th and early C20th in Forbes. Another traditional Chinese game, Mah Jong, is still played in the Shire. Chinese may also have been involved in horse racing in Forbes, and in football and cricket, as they were in other inland communities. Harry Fay, the proprietor of the Hong Yuen store in Inverell, for example, sponsored the local football team and employed many of the players. The store also sponsored a local cricket team in the 1930s (Wilton 2004, p. 61).

The Chinese community brought with them many religious beliefs and practices which they would have enacted at their joss houses, or temples in Forbes and elsewhere. Joss houses, whether they were improvised structures on the goldfields or ornate brick or stone structures in towns, were places of worship and usually dedicated to family or clan ancestors and/or to traditional Chinese deities. These included “Cai Shen (the God of Wealth), Guan Yin (the Goddess of Mercy), Guan Di (the God of Loyalty and protection from injustice) and Tian Hou (Goddess of the Sea)” to whom believers prayed “for health, prosperity, safety and good fortune” (Mo Xiangyi and Wang Jingwen 2009). Joss sticks, or incense, were ritually burned as part of these religious practices. The term “joss” is believed to be a corruption of the Portuguese (and Latin) word for god: deus. There is now no physical evidence of Chinese temples in Forbes Shire, but they would have undoubtedly existed from the 1860s. Such places of worship have been documented in Wyalong, Wagga, Deniliquin, Hay, Albury, Narrandera, Grenfell, Moree, Tingha, and Warren, for example (McGowan 2005; Wilton 2004, p. 85), and there is no reason to think that Forbes would have been without at least one “joss house” or temple in the nineteenth century.

A report of a visit to “the new joss house” in Fitzmaurice Street, Wagga Wagga, in 1887, by a journalist for the Wagga Wagga Advertiser gives us an insight into Chinese religious practices in inland NSW at this time. According to the reported, this temple contained “some very strange symbols of the mysterious doctrine of Confucius”:

[It] was lit up with many candles and lanterns, and Chinese religious devices and symbols, totally beyond our power of description. Several priests, clad in silken robes, officiated at the strange services whilst a tremendous din of gongs, timbrels, and sundry musical instruments of Chinese make seemed to impress … .notwithstanding the semi-suffocating atmospheres of burning incense (in Sherry Morris, ‘The Chinese quarter in Wagga Wagga’, Wagga Wagga and District Historical Society newsletter, 76, June/July 1992, pp 5-6, cited in Wilton 2004, p. 89).

Joss houses in the Forbes Shire may not have been as sophisticated as this temple, but the practices may have been very similar, and would have meant a great deal to believers.

Other religious traditions which would have been practised in Forbes include the annual Ch’ing Ming or Qingming festival, often translated as Tomb Sweeping Day and the Clear Brightness Festival, when people traditionally visited the graves of their ancestors and hosted banquets (Wilton 2004, p. 96-97). Some of the Forbes Chinese may also have been members of a Chinese Masonic Lodge or Society. Buildings associated with these lodges were constructed in many rural towns, including Albury, Hay and Tingha (Wilton 2004, p. 97), but there is no evidence of such a premises in Forbes. Members of the Chinese community may also have belonged to various Christian congregations in Forbes at this time, especially to evangelical Protestant sects.

2.7 The shadow: prejudices and vilification

The notorious ‘Roll Up’ banner which was unfurled at Lambing Flat in the early 1860s when European mobs attacked the Chinese diggers on the gold fields. This banner is now in the Young Historical Museum. Courtesy Wikimedia.

Even though relationships between Chinese and non-Chinese groups appear to have been generally harmonious in the Forbes Shire during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinese settlers nevertheless suffered from racial stereotyping and xenophobia, and were the victims of racial violence and vilification, as they were elsewhere in Australia. This is the dark side of the Shire’s multicultural heritage.

Many of the Lambing Flats (Young) diggers and traders moved on to the Lachlan goldfields after the racial riots of 1861 and brought all their prejudices with them. Racially motivated violence on the scale of that which occurred at Lambing Flats does not seem to have taken place at Forbes in the 1860s, however. Both non-Chinese and Chinese settlers were undoubtedly involved in violence amongst themselves on the goldfields, of course, and Chinese may also have been involved in bushranging activities: one of the most prominent bushrangers on the Gulgong goldfields was a Chinese man, Sam Poo, for example (Williams 1999, p.46).

There are many stories about what Barry McGowan calls “the usual array of taunts, cowardly assaults and bullying” (McGowan 2005) against the Shire’s Chinese residents in the later C19th. One such assault had particularly tragic consequences. In 1893, for example, Jimmy Ah Duck, a 28 year old market gardener who rented land from the Heinkes at Willodene, was walking with his cousin Peter Ah Lee to William Ah Foo’s property on the Bedgerebong Road when, according to Mr Ah Duck’s English wife, Eliza, a group of larrikins started taunting them and calling them “‘Chinese b___d and other bad names”. One of these young “larrikins” was an 18 year old labourer, Frederick Peasley, the son of Thomas and Sarah Peasley of the Welcome Home Inn near what is now known as Chinaman’s Bridge on the Bedgerebong Road. Young Frederick allegedly threw a punch at Jimmy Ah Duck and struck him in the eye after vilifying him: Jimmy Ah Duck allegedly responded by stabbing Peasley with the knife he was using to cut tobacco. Frederick Peasley died from his wound, and Jimmy Ah Duck was so traumatised and shamed by what had occurred that he went home, wrote a will and then quietly overdosed on opium (Forbes and Parkes Gazette 1893; Forbes Family History Group Undated, Jill Peasley, 1997, pp 549-550). Both Frederick Peasley and Jimmy Ah Duck were buried in the Forbes cemetery, but the site of Mr Ah Duck’s grave is now unknown (see section 2.1).

Further research may reveal other tragic conflicts in the Forbes Shire similar to those that occurred elsewhere along the Lachlan. In 1895 at Hillston, for example, on the day after Chinese New Year, a group of Euro-Australians visited Chong Lees’ market garden on the river next to a Chinese camp where up to 40 men were living. Some of the Euro-Australians were drunk and began to steal fruit from Chong Lee’s trees. The Chinese protested but were ignored. A fight broke out and the non-Chinese were driven away. The two groups were joined by their mates and met again on the bridge across the river where violence erupted a second time: “One Chinese man was killed and three severely wounded. Ten Europeans were brought to trial, but they were all acquitted of manslaughter” (McGowan 2005).