[This article was self-published as a pamphlet on the eve of the 1991 NSW election with the support from Greenpeace Australia’s Toxic Waste Campaign, after the Sydney Morning Herald refused a shorter version as ‘too political’.]

It’s your typical Australian family farm. Old weatherboard house with bullnose verandah, corrugated iron rainwater tanks, pepper trees, dam, windmill, sheep dogs at the gate, sheds, large tractors, ploughs, harvester – and at the back door, a large pair of very dusty elastic sided boots and a battered akubra hat. Alongside these icons, the next generation’s little red pedal-power tractor and two tiny blue gumboots.

This is “Yandilla”, home to Christine and Lloyd Nock, their two-year-old son Rory, and to three-month-old daughter Tegan. Lloyd’s parents, Margaret and David Nock, live within cooee in a brick house they built 18 years ago after a few good crops. Both houses are built on a hill overlooking rolling farm land. Here the air is crisp and unpolluted, some of the clearest air in the world, according to astronomer Dr Alan Wright who directs the Parkes Radio Telescope about 50 kms to the north-east.

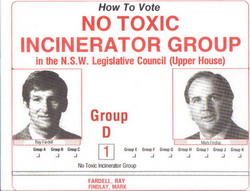

How To Vote leaflet distributed by members of the single issue party, No Toxic Incinerator Group, at the 1991 NSW State Election. The two candidates were Ray Fardell, President of the Bogan Gate Concerned Citizen’s Group, and Mark Findlay, Vice-President.

To the Nocks, this is God’s own country. But to Federal Minister for the Environment, Ros Kelly, and her state counterparts, Tim Moore, in NSW, and Steve Crabb, in Victoria, it is one of seven proposed sites for the yet-to-be-designed High Temperature Incinerator which will, in theory, consume the nation’s 12,000 tonne stockpile of organochlorines, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and hexachlorobenzene (HCBs), and up to 80,000 tonnes of ozone depleting CFC gas.

The proposed site is 2 km from Bogan Gate village, in central NSW, on Commonwealth land between the district grain terminal and “Yandilla’s” boundary fence. Just inside the fence, a portable auger and wheat bin tell the world how Christine and Lloyd and their neighbours feel about being asked to carry the can for the nation’s addiction to toxic chemicals. The auger represents the incinerator stack, which the Nocks believe will contaminate their clean air and their soil and water with dioxins, dibenzofurans and other bioaccumulative toxic compounds: in huge letters across the bin are the words (with appropriate graphics): Give toxic stack the boot.

On the other side of Bogan (as the locals call the village), another field bin reads “Message to Cobb/Armstrong: Incinerator in – you’re out”. Even in this safe National Party seat, it is a message neither the Member for Lachlan and Minister for Agriculture, Ian Armstrong, nor the Federal Member for Parkes, Michael Cobb, can ignore.

In Bogan Gate an abandoned general store wears a bold anti-tox mural, and across the road, at the arts and craft shop which was once the village railway station, grey-haired members of the Country Women’s Association, the very bastions of rural society, talk over their knitting about being prepared to stand in front of the bulldozers if necessary.

Around Bogan Gate (population 200 on a good day), state and federal politicians would have to be both blind and deaf not to get the message: most of the citizens of this small rural community do not want a toxic waste incinerator in their back paddock. And they don’t want a toxic waste incinerator in anyone else’s back paddock either.

At a protest meeting in nearby Forbes on January 15, 1991, an estimated 500 people, most of them traditional country folk, called unanimously on the Federal and State Governments to suspend their activities in seeking a site for a toxic waste incinerator, and to provide the resources to warehouse existing toxic chemicals until more appropriate sunrise technologies are developed to safely destroy the stockpiles. These country people are effectively setting the state and federal agendas for all future discussion about what to do with toxic waste in Australia. Many, like the Nocks, see only political expediency in the decision to shortlist seven sites in five isolated rural communities after the commitment to build the incinerator at Corowa, an irrigation town on the Murray River, was reversed in late 1990.

In a joint statement issued on September 25, 1990, Tim Moore, NSW Minister for the Environment, Andrew McCutcheon, then Victorian Minister for Planning and Urban Growth, and Ros Kelly, Federal Minister for the Arts, Sport, the Environment, Tourism and Territories “congratulated Corowa on their successful submission for the High Temperature Incinerator.”

“The construction of the incinerator will bring many benefits to Corowa, and when it is in operation, the facility will solve one of Australia’s most pressing environmental problems,” the Ministers said.

The Corowa solution to this pressing problem was short lived. When the local paper carried the headlines “Corowa Wins Toxic Incinerator” it precipitated a popular revolt, which no amount of government sponsored “public consultation” could reverse. After a textbook exercise in People Power led by the Corowa and District Concerned Citizens Association, that town was “de-selected” as the incinerator site.

That was how Bogan Gate, and other small communities near Walgett, Moree, Cobar and Ardlethan, ‘won’ consideration as potential incinerator sites. In each of these communities, the Corowa scenario has been repeated. Again country people refused to accept that a toxic waste incinerator would be good for them, and in each of these communities Concerned Citizens Associations emerged like mushrooms after rain. At farm gates, across kitchen tables and at the counters of small general stores throughout the inland, farmers and townsfolk are asking ‘If it’s so safe, why don’t they build it in Sydney?’

The answer, as given by NSW Waste Management Authority’s Merv Tebbutt at one of the public consultation meetings at Bogan Gate in December 1990, has become a rallying cry: “City people wouldn’t have it,” he is alleged to have said.

“That makes us look pretty stupid,” commented Christine Nock, as she breastfed baby Tegan at the kitchen table.

At the Rotary District 970 Conference in Parkes in March, 1991, Tim Moore, the NSW Minister for the Environment, explained the political dilemma in more detail: “The previous NSW government tried to locate such a facility in an urban area and failed. We have inherited such a balls-up situation that it is now practically impossible to sell the idea to an urban area.”

And it seems that country people have become just as intractable as their city cousins. The government can’t sell them a toxic waste incinerator either!

“They say incineration is safe, but what if we couldn’t sell our wheat and sheep?” Christine Nock asked. “And if anything happened, what about us and our kids? No-one knows what the long term effects would be,” she said. “We’ve got to think about these things.”

“The politicians completely underestimated country people,” Bogan Gate Concerned Citizen’s Vice President and conservation farmer, Mark Findlay, explained. His property “Bonnie Doon” is three kilometres from the proposed site.

“They completely failed to comprehend the fabric of rural society. They welded together a tripartisan agreement in Canberra, Sydney and Melbourne that the incinerator was the national answer to toxic waste, and that for political reasons it had to go in the bush. So they won support from the hierarchy of rural based organisations, like the National Farmers Federation, the Country Women’s Association and the National Party, and thought that was enough. But now they’ve got to listen to us. We are forcing change from the bottom, from the grassroots.”

That grassroots pressure is being felt most keenly by Deputy Premier Wal Murray and by Minister for Agriculture Ian Armstrong. Four of the communities proposed as sites are in or near Wal Murray’s Barwon electorate; a further two, including Bogan Gate, are associated with Lachlan, the electorate represented by Ian Armstrong. In recent months, Armstrong has suffered three motions of no confidence from local National Party branches, including his own, because of his support for the proposed incinerator.

With a state election just days away, both Murray and Armstrong are doing everything possible to reassure their constituencies that the incinerator will never be built in their back paddocks. Indeed, Armstrong claimed, at the annual meeting of the Bogan Gate Branch of the National Party in April, that the incinerator had “a snowflake’s chance in hell” of being built in his electorate. He has now identified four bores within 2.5.km of the Bogan Gate site which, he claims, will disqualify it “on technical grounds”.

Murray has also ruled out the four sites associated with his electorate. While campaigning in central western NSW on May 10, 1991, he admitted that country people were justified in asking why the proposed toxic waste incinerator could not be built in Sydney if it were so safe. For political reasons, Armstrong and Murray have now effectively deleted six proposed sites from the list of seven: the only remaining site is a disused mine at Canbelego 46 km west of Cobar in the Broken Hill electorate, which is marginally held by the ALP’s Bill Bechwirth. With only a 2% swing required to displace him, Bechwirth is very vulnerable to grassroots pressure. Like the National Party members, he is now responding to that pressure by openly opposing construction of the incinerator in his electorate.

The NSW elections have given the anti-incinerator lobby an exquisite opportunity to exert pressure. It has also meant that Bogan Gate and Districts Concerned Citizens can now put their message onto 3.5 million ballot papers instead of just a few roadside wheat bins.

At the first hint of an election date, Concerned Citizens President Ray Fardell, Vice-President Mark Findlay, and their Concerned Citizens colleagues throughout rural NSW (including Corowa), registered a new single-issue political party which, not surprisingly, they called No Toxic Incinerator Group (NOTOX for short). ‘No Toxic Incinerator’ is now printed on every Upper House ballot paper: the next step is to win about 200,000 votes to put Ray Fardell, Trundle farmer, father of six, Duntroon graduate, Vietnam veteran and retired Lt. Colonel, into the Upper House of the Parliament of Australia. Mark Findlay is No. 2 on the new party’s ticket.

“We are asking people to register their concern for the issue by giving us their priority vote in the Upper House and then reverting to their traditional or special preferences,” Ray Fardell explained. “If we are still there towards the end of counting, we will probably be vying with the Democrats for the last Upper House seat,” he said.

To these unlikely Upper House candidates, high temperature incineration is but a sunset technology which, for both environmental and economic reasons, can no longer be considered an appropriate way to dispose of toxic chemicals.

They accept that, because of the limitations of science, it is difficult to establish causal relationships between incineration and health problems, but their kitchen tables are covered with data from reputable institutions, including the US Environment Protection Agency and Greenpeace, about the dangers associated with high temperature incineration and reports of deformities and food chain contamination around British, European and North American toxic waste incinerators.

Concern about these issues pulled these two farmers off their tractors into the public arena, and now that they have examined the issue from both sides, they just scratch their heads in wonder at how any government could have committed millions of dollars to this technology, and to all the associated infrastructure, to burn just 12,000 tonnes of concentrated toxic waste – less than half a shipload of wheat to Iraq, and a fraction of the capacity of the Bogan Gate grain terminal. To Ray Fardell and Mark Findlay, the incinerator proposal seems preposterous.

“The only sensible thing to be done now is to remove all seven sites from the threat of the incinerator and build secure above ground storage for the stuff until more appropriate sunrise technologies are developed to deal with it,” Fardell said. “Australia could lead the world in developing environmentally responsible waste management techniques, rather than blindly importing archaic and expensive technology from overseas,” he added.

It seems this message has finally crossed the Blue Mountains and penetrated Macquarie Street. Both Premier Nick Greiner and Deputy Premier Wal Murray are now publicly questioning the need to build the incinerator. Greiner hinted last week that the proposal could be dropped if his government were re-elected. The decision, in theory at least, about where, and if, the incinerator will be built now rests with a government appointed independent committee referred to, in the bush, as Greiner’s Angels. This committee consists of Professor Charles Kerr, Professor of Preventative and Social Medicine at Sydney University; Dr Ben Selinger, Head of the Department of Chemistry and the Australian National University; Michael Davidson, a former National Farmers Federation President and a member of the Federal Government’s Economic Planning and Advisory Council (EPAC); and Wendy McCarthy, a former director of the National Trust (NSW), and chairperson of the National Better Health Program. Their decision was expected in September but may now be delayed for up to two years.

Meanwhile, back at Bogan Gate, the soil is ready for sowing. Next to the proposed incinerator site Lloyd Nock and his fellow farmers are planting the crops city people will, in time, consume as bread, biscuits, beer and breakfast cereals. It’s one of the busiest times of the year in the bush. But it’s also election time, the time, perhaps, to reap the rewards of months of grassroots activism.

By September, the earliest Greiner’s Angels can be expected to make their decision, this year’s lambs will have been born in the paddocks around the proposed incinerator site. If there’s rain at the right time, the crops will be green and lush. And if the Angels decide the nation needs a toxic waste incinerator at Bogan Gate, then under NSW law, there will be an Environmental Impact Study. That could take a further two years. By then it will be Federal election time … As Ian Armstrong says, the incinerator “has a snowflake’s chance in hell.”

Copyright Merrill Findlay, 1991

Personal disclosure, 1991: This article was first published with assistance from Greenpeace Australia. The author, Merrill Findlay, is a freelance writer living in Melbourne and the sister of Mark Findlay who is quoted above.

Merrill spent December 1990/January 1991 on her family’s farm near Bogan Gate to conduct media workshops and a press campaign for Concerned Citizens Groups, and in Sydney to research the issue of high temperature incineration at a more technical level. Naturally she sought a briefing from the NSW Waste Management Authority to understand their position and spent a very valuable morning with Mr Con Zimmerman, WMA’s Waste Management Engineer. Since then, she has maintained close contact with representatives of Concerned Citizens Groups and other organisations and institutions opposed to toxic waste incineration.

Like many other informed people who have considered the issue from many sides, Merrill now believes, for moral, scientific, technological and political reasons, that the Australian Conservation Foundation and other non-governmental organisations that promoted the incinerator concept, made an naive mistake in supporting the Federal Government on HTI. She used this story to help convince the ACF Council to reconsider its support for the toxic waste incinerator. MF 1991.

Content revised March 2004, 5 January 2005, 21 January 2007, and posted on this new web site 5 December 2010.

Permalink: https://merrillfindlay.com/?page_id=697

© This material is subject to copyright and any unauthorised use, copying or mirroring is prohibited by law.