Paper co-authored by Merrill Findlay and Jordan Williams, Centre for Creative and Cultural Research, University of Canberra, ACT, Australia, presented by Merrill Findlay at the Australian Regional Development Conference, 15-17 October 2014, The Commercial Club, Albury, NSW.

[Authors’ version. This paper has been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in the conference proceedings. It is also available at my Rural Arts Festivals blog >>]

Abstract: The biennial Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival founded in Forbes, NSW, in 2010/11, has both intrinsic and instrumental value for the communities it serves, and has catalysed major cultural and social changes in the town. With culture and the creative industries having at last been acknowledged as drivers and enablers of sustainable development, this and other rural arts festivals offer valuable opportunities for collaboration between professionals working in rural and regional development fields and in the creative industries. The potential of rural festivals to enable and drive sustainable development cannot by fully realised, however, until serious capacity deficits are addressed to support the creative industries in small communities, as outlined in UN’s 2013 Resolution 68/223.

Keywords: rural arts festivals, creative industries, arts, creativity, sustainable development, capacity building

In the Spring of 2011 residents of the small inland river town of Forbes, New South Wales, celebrated the end of the Millennium Drought with their first Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival. ‘Boy oh boy, what a weekend’, then-mayor Phyllis Miller enthused in her weekly column in the Forbes Advocate.[1] It was ‘in a word ‘fantastic’,’ the Advocate’s Barry Shine wrote in his Page 1 editorial. ‘No-one could disagree that the culture, colour, enthusiasm and participation exceeded expectations.’[2] The Festival’s Sydney-based creative director, Stefo Nantsou, agreed: ‘given the short lead time, it was extraordinary,’ he said.[3] And in a letter to the Advocate, local landholder Gillian Sweetland, called it ‘an absolute triumph’ and ‘welcomingly inclusive of age, race, creed and ability’:[4]

In the Spring of 2011 residents of the small inland river town of Forbes, New South Wales, celebrated the end of the Millennium Drought with their first Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival. ‘Boy oh boy, what a weekend’, then-mayor Phyllis Miller enthused in her weekly column in the Forbes Advocate.[1] It was ‘in a word ‘fantastic’,’ the Advocate’s Barry Shine wrote in his Page 1 editorial. ‘No-one could disagree that the culture, colour, enthusiasm and participation exceeded expectations.’[2] The Festival’s Sydney-based creative director, Stefo Nantsou, agreed: ‘given the short lead time, it was extraordinary,’ he said.[3] And in a letter to the Advocate, local landholder Gillian Sweetland, called it ‘an absolute triumph’ and ‘welcomingly inclusive of age, race, creed and ability’:[4]

And Sunday’s beautiful bush setting on the [lake] … was brilliant. The festival was jam packed with memorable moments from the welcome to country to the young talent to the lanterns and lotus lights and the chamber opera and the character sketches at the after-party. … My heartfelt thanks to all for so ably showing that the arts are like the river, both are essential to life lines. [5]

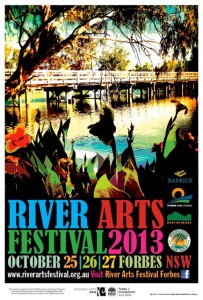

The second River Arts Festival in 2013 was even more enthusiastically received. The three day program included over seventy individual events featuring local and regional visual artists, dancers, poets, musicians of many genres, playwrights, actors and other performers, film makers, crafts workers, dragon boaters, lantern makers and even a dancing horse. An estimated 4,000 people attended the grand finale, a lantern parade around Lake Forbes which morphed into Drumming Up Country, a community music event created by composer and percussionist Peter Kennard.

The second River Arts Festival in 2013 was even more enthusiastically received. The three day program included over seventy individual events featuring local and regional visual artists, dancers, poets, musicians of many genres, playwrights, actors and other performers, film makers, crafts workers, dragon boaters, lantern makers and even a dancing horse. An estimated 4,000 people attended the grand finale, a lantern parade around Lake Forbes which morphed into Drumming Up Country, a community music event created by composer and percussionist Peter Kennard.

‘Spectacular Festival’ the front-page of the Forbes Advocate enthused from beneath a half-page photo of the grand finale. ‘The lanterns have died out, musicians have packed up and gone home, and everyone is recovering after a huge weekend at the 2013 Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival,’ Sophie Harris reported in her lead article. ‘This year’s festival was an astounding success and impressed all who attended the celebration of art and culture in our region.’[6]

Even the sceptics were won over by River Arts 2013, including Councillor Ron Penny, the current mayor of Forbes. After being mobbed by the crowd as he and other councillors carried a giant dragon lantern around the lake, he could finally acknowledge that yes, ‘At the end of the day … this could be the biggest thing for Forbes yet.’[7]

The genesis of this rural arts festival was unique in that it was conceived and driven by one of the few professionals in Forbes Shire’s Creative Industries sector, an independent writer (and lead author of this paper) with sufficient cultural development experience, entrepreneurial and fund raising skills, community credibility and general social capital to enable her to establish a festival independent of Council, and co-create its headline act, a very contemporary chamber opera, The Kate Kelly Song Cycle.[8] Both the first River Arts Festival and its headline act responded to a range of arts-related issues locals raised, including the absence of an arts festival in the region, despite a plethora of cultural festivals of various kinds; the lack of modern cultural amenities in the town; the invisibility of arts, creativity and culture in local and regional planning and development processes at the time; and the relative cultural impoverishment people in small inland communities experienced.

The Festival and chamber opera also responded to a range of social and environmental challenges locals were concerned about in 2010/11 after a decade of drought, including rural poverty, aging and declining populations, social cohesion, depression, suicide, domestic violence, substance abuse, racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination, economic globalisation, land degradation, biodiversity loss, Climate Change, the lack of activities for young people, and reduced educational and job opportunities, for example: the same interconnected challenges small rural communities are facing everywhere.[9]

The Festival’s progressive mission statement reflects these concerns.[10] One of the key values embedded in this document is inclusivity, a commitment which ensures that all, or most, festival events are free to the public and accessible to all groups, and that all groups can creatively participate. This commitment gave Wiradjuri descendants their first opportunity in living memory to tell their own stories, on their own terms, in a mainstream public event in Forbes. This community’s Welcome To Country (WTC) Spectacular has now become one of the Festival’s signature events. The first Spectacular was conceived and produced by Wiradjuri descendant Russell Hill, and performed by students from all schools in the Shire.[11] For both participants and audience members it was cathartic. College student Aiden Clarke’s reading of Kevin Rudd’s Sorry Speech was especially memorable, as was Forbes North Primary School choir’s rendition of I am Australian in both Wiradjuri and English. This first Welcome To Country Spectacular received the River Arts Festival’s first standing ovation.

The second Festival in 2013 coincided with the bicentenary of the first documented crossing of the Blue Mountains which led to the European settlement of Wiradjuri Country and to Aboriginal dispossession.[12] ‘We’ve struggled in the past to try to get our message across in regard to Aboriginal occupation because the past has either been hidden or denied,’ the producer of the 2013 Welcome To Country, Wiradjuri man Larry Towney, said. The Festival Welcome To Country Spectacular ‘provides us with the perfect opportunity to explain what’s happened in the past and do it the way we feel it should be done, from an Aboriginal perspective.’[13]

‘And it changed the attitudes, particularly of the older crowd,’ he continued. ‘They were excited. They wanted to be involved and became very, very proud of who they were. I think it changed the future. It really did change the future, in wanting to move forward.’[14]

Not only is the River Arts Festival ‘changing the future’ for Wiradjuri people in and around Forbes, it is, like other arts festivals, nurturing a new generation of arts makers and arts lovers from other backgrounds, and opening up new and hitherto unimagined opportunities in the town and the region.[15] The Festival has catalysed a new vision of Forbes Shire as a creative hub for the entire region, for example. Indicative of the power of this a vision is the inauguration in 2013, by Forbes Services Memorial Club, of an annual $20,000 acquisitive national sculpture competition, SculptureForbes.[16] Another is the ‘Somewhere Down The Lachlan’ Sculpture Trail conceived and developed by Forbes artist Rosie Wingrove Johnston and supported now by the Services Club, Forbes Arts Society, and Forbes Shire Council.[17] The Sculpture Trail’s first artwork, Pyramid, a controversial bronze by Sydney-based artists Gillie and Marc Schatnter, was unveiled in October 2014 by the NSW Minister for Arts and local member, Hon. Troy Grant.[18] Rosie Wingrove Johnston hopes that the Trail’s very contemporary sculptures will not only have intrinsic value as works of arts, but will also project an image of Forbes as ‘a sophisticated, dynamic, forward thinking town’,[19] and thus attract visitors and new settlers.

That people in a small inland rural shire of just 10,000 people should value the arts and creativity so highly, and personally engage in arts activities with such passion, should not be surprising, because, as the 2014 Australia Council for the Arts report, Arts in Daily Life: Australian Participation in the Arts, confirmed, more people actually participate in the arts in Australia than they do in sports! As Chair of the Australia Council, Rupert Myer, recently commented, ‘It’s time we outed our national love affair with the arts. They’re not a niche activity. Instead they are all but universal in Australians’ lives.’ [20]

In responding to the Arts in Daily Life research, the authors of the Australia Council’s new strategic plan observed that ‘Australians demand opportunities to gain access to and participate in the arts, be it as consumers or creators.’[21] But when our ‘demands’ for these opportunities go unanswered, people have to either go without, or, as occurred in Forbes, create opportunities for themselves to fill the gaps left by the arts policy failures of all tiers of government. Because, as Gillian Sweetland, reminds us, ‘the arts are like the [Kalari-Lachlan] river, both are essential to life lines.’[22]

According to the Australia Council report, nearly half of all Australians personally create arts or craft works, or perform artworks on stage or elsewhere, in their everyday lives, while 85 percent of Australians believe that the arts enrich their lives and made their lives more meaningful. More than half of those interviewed for the Australia Council report also believed that the arts help people cope with stress, anxiety and depression and increased their sense of well-being and happiness. More than forty percent agree that ‘the arts has a big or very big impact in raising awareness about difficult issues facing our society’.[23] Only five percent of people claimed that they had not engaged with the arts and crafts in the twelve months preceding the survey, although they had surely encountered live or recorded music or visual images in this time.

The report also revealed a strong correlation between people’s appreciation of the arts and engagement in arts activities as adults and their experience of the arts as children, a finding which emphasises the importance of free and committedly inclusive arts festivals in rural Australia to overcome the many barriers to arts participation that still remain. Adults who did not experience the arts as children tended to believe that the arts were not part of their self-image, or identity, and/or gave other reasons for not engaging with the arts, such as opportunity costs, or access barriers including distance, lack of people to accompany them, poor health or disability.[24] This was especially so for people living in regional Australia.[25] Unfortunately the report did not differentiate between regional and rural Australia, so we don’t know how people in small rural shires like Forbes felt.[26]

Anecdotal evidence from the River Arts Festival confirms that engagement with literature, dance, music, sculpture, theatre, film and other art forms, and active participation in arts-making activities, is intrinsically important to country people because they derive pleasure, personal fulfilment, shared meanings or sense of belonging, empathetic understandings, and intellectual stimulation from these activities.[27] But the arts, arts festivals, and the creative industries also have instrumental value in rural communities, as means to non-arts ends,[28] as the comments by Wiradjuri man Larry Towney, artist Rosie Wingrove Johnston, the once-sceptical mayor of Forbes, Ron Penny, and the growing cache of academic literature and official reports confirm.[29]

At the same time that the River Arts Festival was emerging in Forbes, the United Nations system was gearing up for its mighty Rio+20 Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012 to review the progress (or lack of it) that UN member states had made in the twenty years since the United Nations 1992 Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro. This first Rio Conference came just five years after the World Commission on Environment and Development’s landmark report, Our Common Future, which introduced the concept of Sustainable Development and famously defined it as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.[30] Surprisingly, culture, creativity and their many tangible and intangible manifestations were not mentioned at this first Rio conference, and barely mentioned in the official Rio+20 proceedings either, notwithstanding then already existent literature on the importance of culture, the arts and creativity in achieving ‘sustainability’ outcomes.

These silences in mainstream sustainability discourses ignited a global campaign by international arts, cultural and local government organisations, such as the global network United Cities and Local Governments Committee on Culture,[31] the International Federation of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies (IFACCA), and UNESCO, to ensure that culture and the creative industries were explicitly acknowledged as enablers and drivers of sustainable development and be integrated into all future sustainability planning and development policy processes.[32] The advocacy campaign was successful. On 20 December 2013 the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 68/223 on Culture and Sustainable Development which invited all member states to, amongst other things, ‘ensure a more visible and effective integration and mainstreaming of culture into social, environmental and economic development policies and strategies at all levels’; and, most importantly for small country towns, such as Forbes, to

promote capacity-building, where appropriate, at all levels for the development of a dynamic cultural and creative sector, in particular by encouraging creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship, supporting the development of cultural institutions and cultural industries, providing technical and vocational training for culture professionals and increasing employment opportunities in the cultural and creative sector for sustained, inclusive and equitable economic growth and development.[33]

This global conversation about culture, creativity, the creative industries and sustainability continues. In an address to the General Assembly’s High Level Thematic Debate on Culture and Development in May 2014, UNESCO’s Director-General, Irena Bokova, emphasised the ‘double nature of culture, at the same time enriching our identity and providing the means for sustainable development’, for example. She insisted that ‘a context-sensitive and culture-smart approach is an essential enabler of sustainable development, a cross-cutting driver for all development efforts.’ [34]

The integration of culture and the creative industries into sustainable development thinking represents a paradigm shift not only in social and economic policy thinking, but also in the arts and creative industries sectors. The Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival, and other rural cultural events, offer many new and exciting opportunities for ‘context-sensitive and culture-smart’ collaboration between these sectors.

There can be no doubt that the River Arts Festival is already enriching people’s lives and ‘changing the future’ in Forbes and neighbouring shires, albeit in modest ways. It has the potential, however, to become a regionally, even nationally significant arts event which could not only serve the creative needs and aspirations of people along the full length and breadth of its river valley and neighbouring catchments, but also enable and drive transformative change throughout inland New South Wales. This potential cannot be realised, however, until critical capacity deficits are addressed in Forbes and other small inland towns. Creative industry professionals and volunteers in these communities, whatever their cultural backgrounds, need comprehensive capacity building support from all tiers of government if they are to develop the skills, networks and support structures necessary to grow and manage regionally and nationally significant arts events to enrich people’s lives, and drive and enable sustainable development. And why shouldn’t country people enjoy the same cultural opportunities that city folk now take for granted?

References

Argent, N., M. Tonts, et al. (2014). ‘A creativity-led renaissance? Amenity-led migration, the creative turn and the uneven development or rural Australia.’ Applied Geography(44): 88-98.

Australia Council (2014). Arts in Daily Life: Australian Participation in the Arts. Sydney, Prepared for the Australia Council by the market research company instinct and reason.

Australia Council for the Arts (2014). A culturally ambitious nation: strategic plan 2014 to 2019. Sydney, Australia Council and the Australian Government.

Bokova, I. (2014). Address by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO on the occasion of the General Assembly High Level Thematic Debate on Culture and Development: DG/2014/061. New York, UNESCO.

Duxbury, N. and H. Campbell (2011). ‘Developing and revitalizing rural communities through Arts and Culture.’ Small Cities Imprint 3(1): 111-122.

Gibson, C., G. Waitt, et al. (2010). ‘Cultural Festivals and Economic Development in Nonmetropolitan Australia.’ Journal of Planning Education and Researach 29(3): 280-293.

McCarthy, K. F., E. H. Ondaatje, et al. (2004). Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the debate about the benefits of the arts. Santa Monica, CA, The Wallace Foundation and RAND Research in the Arts

Myer, R. (2014). Exposing Australia’s love affair with the arts. National Arts Agency News, IFACCA.

Pascual, J. (2013). Cultural Policies, Human Development and Institutional Innovation: or Why we need an Agenda 21 for culture. Sustaining Cultural Development: Unified Systems and New Governance in Cultural Life. B. Mickov and J. Doyle, Gower: 55-65.

SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd (2013). Valuing Australia’s Creative Industries: Final Report, Creative Industries Innovation Centre.

UN General Assembly (2014). Culture and sustainable development: Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 20 December 2013 68/223. Sixty-eighth session, Agenda item 21. New York, United Nations.

UNESCO (2013). The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Polcies. Paris, UNESCO.

UNESCO and UNDP (2013). Creative Economy Report, UNESCO and UNDP.

Western Research Institute (2009). Central West Creative Industries Survey. Bathurst, Arts OutWest.

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our Common Future, Oxford University Press.

END NOTES

[1] From the Mayor’s desk, Phyllis Miller, Forbes Advocate, 10 September 2011.

[2] Barry Shine, Forbes Advocate, 6 September 2011, p. 1.

[3] Letter to Merrill Findlay and the Festival committee, 25 October, 2011.

[4] Gillian Sweetland, Festival Triumph, Forbes Advocate, 27 September 2011, p. 7.

[5] ibid.

[6] Sophie Harris, Spectacular Festival, Forbes Advocate, 29 October 2013, downloaded 25 August 2014 from http://www.forbesadvocate.com.au/story/1871970/spectacular-festival/.

[7] Sponsorship thanks, Forbes Advocate, 25 February, 2014, p. 4.

[8] The Kate Kelly Song Cycle by composer Ross Carey and librettist Merrill Findlay, Forbes, 2011. See merrillfindlay.com.

[9] Duxbury, N. and H. Campbell (2011). ‘Developing and revitalizing rural communities through Arts and Culture.’ Small Cities Imprint 3(1): 111-122. Argent, N., M. Tonts, et al. (2014). ‘A creativity-led renaissance? Amenity-led migration, the creative turn and the uneven development or rural Australia.’ Applied Geography(44): 88-98.

[10] Our Festival Mission, Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival Inc., last updated 24 June 2013, downloaded 25 August 2014 from http://riverartsfestival.org.au/?page_id=2086.

[11] Welcome to Country 2011, Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival Inc., last updated 19 December 2013, downloaded on 25 August 2014 from http://riverartsfestival.org.au/?page_id=339

[12] Welcome To Country 2013, Kalari-Lachlan River Arts Festival Inc., downloaded 25 August 2014 from http://riverartsfestival.org.au/?page_id=4663

[13] Interview with Merrill Findlay at Lachlan Catchment Management Authority, Forbes, 31 January 2014.

[14] ibid.

[15] Gibson, C., G. Waitt, et al. (2010). ‘Cultural Festivals and Economic Development in Nonmetropolitan Australia.’ Journal of Planning Education and Researach 29(3): 280-293. P. 281.

[16] Sculpture Forbes, Forbes Services Memorial Club 2014, downloaded 24 August 2014 from http://sculptureforbes.com.au/about-the-competition/

[17] Sophie Harris, ‘Council says ‘yes’: Albion Park will be home to sculptures’, Forbes Advocate, 26 August 2014, downloaded 26 August 2014, from http://www.forbesadvocate.com.au/story/2513438/council-says-yes-albion-park-will-be-home-to-sculptures/?cs=719; Sophie Harris, ‘Sculpture hot topic at council meeting’, Forbes Advocate, 21 August 2014, downloaded 26 August 2014, from http://www.forbesadvocate.com.au/story/2503712/sculpture-hot-topic-at-council-meeting/?cs=719

See ‘Somewhere down the Lachlan, Forbes Arts Society, 2014, downloaded 24 August 2014, from http://www.forbesartssociety.com/#!sculpture/c1rd6;

[18] See http://www.forbesadvocate.com.au/story/2299437/sculpture-trail-to-be-amazing/?cs=722 and http://www.forbesadvocate.com.au/story/2299438/first-pyramid-sculpture-given-the-go-ahead/?cs=722, last accessed 25 August 2014.

[19] Rosie Wingrove Johnston, in an address to a meeting of Forbes Shire Council on 22 August 2014.

[20] Myer, R. (2014). Exposing Australia’s love affair with the arts. National Arts Agency News, IFACCA.

[21] Australia Council for the Arts (2014). A culturally ambitious nation: strategic plan 2014 to 2019. Sydney, Australia Council and the Australian Government.

[22] ibid.

[23] Australia Council (2014). Arts in Daily Life: Australian Participation in the Arts. Sydney, Prepared for the Australia Council by the market research company instinct and reason. p. 33-34

[24] Ibid. P. 10-11, 37

[25] Ibid. P. 80

[26] Ibid. P. 86

[27] McCarthy, K. F., E. H. Ondaatje, et al. (2004). Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the debate about the benefits of the arts. Santa Monica, CA, The Wallace Foundation and RAND Research in the Arts , Chapter 4, Intrinsic benefits: the mission link, pp. 37-52

[28] Ibid., Chapters 2 & 3 on Instrumental benefits.

[29] See, for example, Western Research Institute (2009). Central West Creative Industries Survey. Bathurst, Arts OutWest.; SGS Economics and Planning Pty Ltd (2013). Valuing Australia’s Creative Industries: Final Report, Creative Industries Innovation Centre.; UNESCO and UNDP (2013). Creative Economy Report, UNESCO and UNDP.;

[30] World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our Common Future, Oxford University Press. In Australia we called it Ecologically Sustainable Development, or ESD.

[31] Pascual, J. (2013). Cultural Policies, Human Development and Instututional Innovation: or Why we need an Agenda 21 for culture. Sustaining Cultural Development: Unified Systems and New Governance in Cultural Life. B. Mickov and J. Doyle, Gower: 55-65.

[32] See, for example, UNESCO (2013). The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Polcies. Paris, UNESCO.

[33] UN General Assembly (2014). Culture and sustainable development: Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 20 December 2013 68/223. Sixty-eighth session, Agenda item 21. New York, United Nations.

[34].Bokova, I. (2014). Address by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO on the occasion of the General Assembly High Level Thematic Debate on Culture and Development: DG/2014/061. New York, UNESCO.

Page created 19 June 2014. Last revised 21 October 2014.

Permalink https://merrillfindlay.com/?page_id=3766